Karl Barth is the most famous (and infamous) opponent of Natural Theology in the world. However, in the final volume of the Church Dogmatics, Barth developed a Natural Theology of his own, that he titled "Secular Parables of the Kingdom" (c.f. CD IV/3.1, §69.2 The Light of Life). Did Barth flip-flop on Natural Revelation in the twilight years of his life? Reactions to Barth's Secular Parables have ranged in a broad spectrum from those who say he completely contradicted what he had opposed for thirty years or more, to those who say his Secular Parables is completely consistent to what Barth had said since the beginning. In what follows is an exploration into Barth's 'No!' to Natural Theology, and an explanation of what Barth meant by "Secular Parables" in this final decisive word on Natural Revelation and Natural Theology.

Karl Barth is the most famous (and infamous) opponent of Natural Theology in the world. However, in the final volume of the Church Dogmatics, Barth developed a Natural Theology of his own, that he titled "Secular Parables of the Kingdom" (c.f. CD IV/3.1, §69.2 The Light of Life). Did Barth flip-flop on Natural Revelation in the twilight years of his life? Reactions to Barth's Secular Parables have ranged in a broad spectrum from those who say he completely contradicted what he had opposed for thirty years or more, to those who say his Secular Parables is completely consistent to what Barth had said since the beginning. In what follows is an exploration into Barth's 'No!' to Natural Theology, and an explanation of what Barth meant by "Secular Parables" in this final decisive word on Natural Revelation and Natural Theology.

What is Natural Theology?

Karl Barth said "Natural theology is the doctrine of union of man with God existing outside God's revelation in Jesus Christ." (CD II/1)[1]. It is possible to discern scientific, mathematical and philosophical truths through the study of the natural world, however (according to Barth), knowledge of God may not be ascertained in this way. The natural world is not source of a "Natural Revelation" like a "second Bible" in which anyone may devise a "Natural Theology" independent of God's self-Revelation in Jesus. Therefore, any "Natural Theology" that is based on any "Natural Revelation" apart from the threefold witness of the Word of God, namely Jesus, is strictly rejected by Barth.

"One would think that nothing could be simpler or more obvious than the insight that a theology which makes a great show of guaranteeing the knowability of God apart from grace and therefore from faith, or which thinks and promises that it is able to give such a guarantee—in other words, a "natural" theology—is quite impossible within the Church, and indeed, in such a way that it cannot even be discussed in principle." —Karl Barth, CD II/1 [2]

Natural Theology has many aliases, such as "General Revelation" (in contradistinction from "Special Revelation") or "Common Grace" or "Nature and Grace" and other rubrics; Barth raged against all forms of Natural Theology as such.

A Brief Historical Introduction

In 1932, in the very beginning of the Church Dogmatics (CD I/1 preface), the first thing Barth says is that "so-called natural knowledge of God" (e.g. analogia entis) "is the invention of the antichrist." Barth adamantly taught that there is no knowledge of God apart from the self-revelation of God alone. Any other source of revelation is strictly rejected by Barth as Natural Revelation, and any Natural Theology based on Natural Revelation is likewise rejected by Barth because Barth says there is no such thing as a "theology from below" [3] where knowledge of God may be obtained from observing sticks and stones (as in the natural sciences) or triangles (as in mathematics) or any other name apart from the name above all names "Jesus" (Phil 2:9).

In 1934 (two years after CD I/1), Emil Brunner wrote "Nature and Grace" that allowed for a limited form of Natural Theology, to which Barth wrote a scolding rebuke titled "Nein!" (No!) that even included "An angry introduction." This 1934 Natural Theology correspondence with Brunner, was so vicious that it ended their friendship for the rest of their lives. Many have criticized Barth for this response, however this sacrifice of friendship may have been necessary because Barth's 'No!' to Natural Revelation was intimately connected to his 'No!' to German Christians in Nazi Germany.

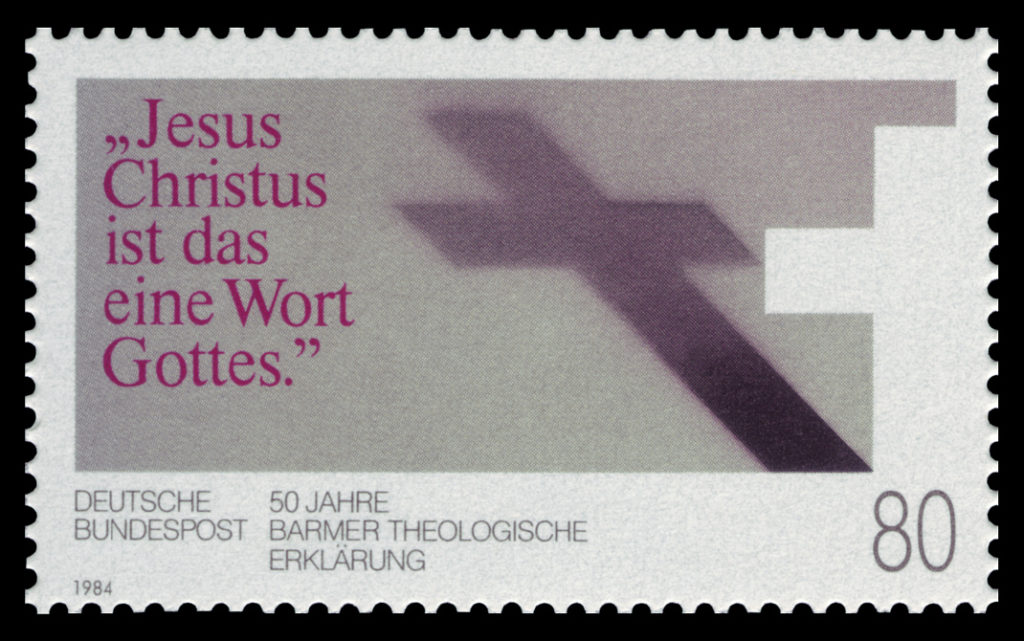

The Reich Church had called for Hitler's Mein Kampf to be placed next to the Holy Bible as a secondary source of revelation; so Barth's protest against Natural Revelation was also a protest against the Nazi claim to be a revelation of God. Barth protested against all such forms of Natural Revelation (especially the Nazi kind) in his contributions to the Barmen Declaration (1934) which says in "8.12 We reject the false doctrine, as though the church could and would have to acknowledge as a source of its proclamation, apart from and besides this one Word of God, still other events and powers, figures and truths, as God's revelation."In 1940, Barth fully expounded his rejection of Natural Revelation, and any Natural Theology built upon it, in the Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of God, Vol. II/1. (This is the very first volume of the Church Dogmatics that I personally have read and Hans Urs Von Balthasar believed it was the best volume in the entire Church Dogmatics.) In this volume, Barth silences any objection appealing to the 'divine nature' in Romans 1:20, or Psalm 19 or 140, or Job 38-40. Barth's refutation of Natural Revelation stood impregnable.

However in 1959, almost two decades later, in the final complete volume of the Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of Reconciliation, Vol. IV/3.1, Barth surprised the world by developing his own Natural Theology that he called the "Secular Parables of the Kingdom" (c.f. CD IV/3.1, §69.2 The Light of Life) because Barth now appeared to affirm substantially what he strongly opposed 25 years prior in his debate with Emil Brunner. Many accused Barth of affirming Natural Revelation in the end, such as Jürgen Moltmann who accused Barth of coming to "the same result" as "his intimate enemy" Emil Brunner in 1934. However, 15 years had past since Nazi Germany was smote in its ruin (as Gandalf might say), so the political situation had changed in post-World War II Germany. CD IV/3.1 was written at a time that Barth could freely add clarifications that were consistent with what he had written since he began the Church Dogmatics I/1 in 1932 without Nazis overhead.Lastly in 1966 as Brunner laid dying, Barth made an attempt to reconcile with Emil Brunner, by writing him a letter that said: "If he [Brunner] is still alive and it is possible, tell him I commend him to our God. And tell him the time when I thought I should say No to him is long since past, and we all live only by the fact that a great and merciful God speaks his gracious Yes to all of us." Barth's attempt may have been too little too late, but these words may not be ignored.

Secular Parables of the Kingdom

Secular Parables explained in a nutshell

In a 2009 interview, Jurgen Moltmann's provided this helpful summary of Barth's Secular Parables:

"At the end of his Church Dogmatics, he [Karl Barth] developed his own Natural Theology. After the special Christian Theology, there can and must be a theology of nature about the many lights outside of the one light of Christ, and the many words of truth outside of the One Word of the Incarnate of God, which is Christ. But the relationship between the Light which is Christ and the many lights of the world, is like the rear-reflectors [sic] of your car. If you switch on the lights of your car, then you can see the reflectors of the car in front, so the lights in nature are only a reflection of the Light of Christ. They do not illuminate anything by themselves; only as a reflection of the Light of Christ."

—Jürgen Moltmann[4]

The "Secular" in Secular Parables Explained

Karl Barth's Secular Parables of the Kingdom may be described with light metaphors, so by "secular" Barth refers to any "other" light that does not originate from the divine light of God's self-Revelation in Jesus. For example, the Sun illuminates the Solar System in a similar way to how God's self-Revelation enlightens all people (John 1:9 NRSV). However, there are many other lesser lights in the solar system apart from the light of the Sun that shine their light by reflecting the light of the Sun, such as the Moon and planets. These "secular" lights emit no light of their own, and only generate light by reflecting light; or the Evangelist also says "the light shines in the darkness" (John 1:5 RSV). The Full Moon only provides light because it is reflecting the light of the Sun, but when the light of the Sun does not shine upon the moon, it reflects no light and becomes invisible in the darkness (i.e. New Moon). So according to the Secular Parables there is only one divine light in God's self-Revelation, but there are many other lesser lights in Nature that are outside of God's self-Revelation that also reveal the knowledge of God, but only so far as they reflect the light of God.Barth's "Secular Parables of the Truth" is a Theology of Nature by Reflection (notice how I avoided the contentious term "Natural Theology"); it's background stems from John Calvin's the famous discussion of the knowledge of God in the opening of John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion, and so it's appropriate to use Barth's commentary on Calvin's Catechism to explain how reflection applies to his Secular Parables, and so in the Faith of the Church, Barth says:

What is the nature of the knowledge of God which is given us in the world? Let us beware now: Man has no possibility to know God "through nature." There is no knowledge of God which was given along with the existence and the essence of the world. We ourselves cannot say: God is in the world here or he is there. But God himself is he who, in the world, gives himself to our knowledge, according as he pleases. We notice with what reservations Calvin speaks of this knowledge the world does not stand witness of God but insofar as God wills it and wherever he wills it. It is not the history of any people which witnesses unto God, but the history of Israel, the Bible and Jesus Christ belong to the world. The world then is a mirror that reflects something found elsewhere, that reflects it insofar as God wills it and wherever God wills it.

—Karl Barth, Faith of the Church[5]

Ancient mirrors were often a polished piece of brass, such as this Egyptian bronze mirror (800-100 BCE) [6], and this explains why Paul said we see things dimly in a mirror (1 Cor 13:12).

But this means that we cannot treat them [Secular Parables] like Holy Scripture, even though as true words they can only confirm and illustrate Holy Scripture, even when in a given time and place a few or many or even the majority in the community are convinced of their truth, they cannot be fixed and canonized as the Word of the Lord. That is, they cannot be regarded and proclaimed as a source and norm of knowledge which is valid at all times, in all places, and for all. And they certainly cannot be collected, and assembled as words of universal authority, and as such laid alongside Scripture as a kind of second Bible. They may be issued and received here and there, yesterday, to-day and to-morrow. But neither individually nor corporately can they be given universal and normative authority as a source of revelation. They themselves are opposed to such a process and avoid such a misuse.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[12]

The "Parables" in Secular Parables Explained

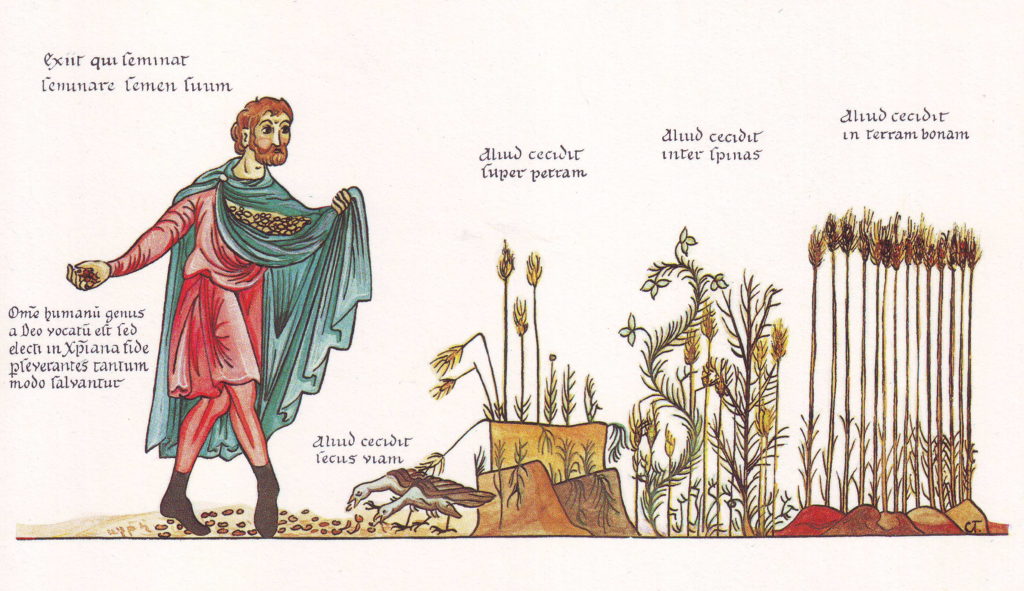

Unfortunately, Barth's Secular Parables is more complicated than a Natural Theology by 'Reflection' because it doesn't require faith to see the Moon in the sky, but it does require faith to recognize God's self-revelation in the world. This is why Barth utilizes the concept of "parables" to explain his Theology of Nature by Reflection. Jesus used parables in his preaching, so that those who have faith would understand and those who do not have faith (i.e. Pharisees) would not understand (c.f. Matt 13:13).

So what does Barth mean by 'parable' when he says "Secular Parables of the Kingdom"? Barth explains that a parable is based on an ordinary human happening that has no significance of its own, such as when we engage in mundane activities such as going to work, eating a meal, or driving a car. These activities may be observable by anyone, and are not self-revelations of God at all, however they have the capacity to reflect divine self-revelation to people through faith.

In sum, the New Testament parables are as it were the prototype of the order in which there can be other true words alongside the one Word of God, created and determined by it, exactly corresponding to it, fully serving it and therefore enjoying its power and authority.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[13]

Barth explains how self-revelation is communicated through natural (or 'secular') parables in the following quotation (n.b. the bold print):

Parables (parabolai) are little stories which it seems anyone might tell of ordinary human happenings. But they are called parables (parabolai) of the Kingdom (basileia), and it is often said expressly that the Kingdom (basileia) is "likened unto" (homoiwthe) these events, or, with an obvious view to this equation, that the events themselves, or the leading characters in them, are "like" the Kingdom (basileia). It is also said that the kingdom in its likeness to these events, or these events in their likeness to the kingdom, can and will be heard by those who have ears to hear, i.e., by those whom it is given to hear (Mark 4:9f.). That is to say, they will hear and receive the equations of likenesses as such, whereas those who are "without" will not perceive and understand what is at issue, namely, the "mystery" of the kingdom. . . . The one true Word of God makes these other words true. Jesus Christ utters, or rather creates, these parables, speaking of the kingdom, of the life, and therefore of Himself, and doing so in stories which it might seem that others could tell, yet which they are unable to do, because His Word alone can equate the kingdom really like them, and makes them like the kingdom in which He tells them, so that the narrative is no mere metaphor but a disclosing yet also concealed revelation—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[14]

Barth's definition of Secular Parables in CD IV/3.1

So now that Barth's conception of 'secular' and 'parable' has been defined, everything explained so far is confirmed with the following quotation form CD IV/3.1 (especially the bold print):

We now turn to the more complicated question of true words which are not spoken in the Bible or the Church, but which have to be regarded as true in relation to the one Word of God, and therefore heard like this Word, and together with it.

Are there really true words, parables of the kingdom, of this very different kind? Does Jesus Christ speak through the medium of such words? The answer is that the community which lives by the one Word of the one Prophet Jesus Christ, and is commissioned and empowered to proclaim this Word of His in the world, not only may but must accept the fact that there are such words and that it must hear them too, notwithstanding its life by this one Word and its commission to preach it.

Naturally, there can be no question of words which say anything different from this one Word, but only of those which do materially say what it says, although from a different source and in another tongue. Should it not be grateful to receive it also from without, in very different human words, in a secular parable, even though it is grounded in and ruled by the biblical, prophetico-apostolic witness to this one Word? Words of this kind cannot be such as overlook or even lead away from the Bible. They can only be those which, in material agreement with it, illumine, accentuate or explain the biblical witness in a particular time and situation, thus confirming it in the deepest sense by helping to make it sure and concretely evident and certain.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[15]

Barth provides no examples of Secular Parables

Karl Barth was unwilling to provide any examples of Secular Parables and criticized Zwingli for doing so. This is the shakiest part of Barth's Secular Parables of the Kingdom, because his unwillingness to provide a valid example of his doctrine, calls into question whether he actually does affirm that Secular Parables exist. So Barth's Theology of Nature by Reflection may be nothing more than the smile of the Cheshire Cat, which is the last thing to disappear of this vanishing fictional feline. Opponents of Natural Theology may seize upon Barth's words as follows to assert that Barth has been consistently against Natural Theology and all its derivatives since the very beginning.In conclusion, it is to be noted that, surprising though it may seem, in our whole development of the problem of these other words we have not adduced a single example, nor quoted a single name, nor mentioned an event or trend or movement, nor referred to a new and singular or common and general phenomenon in political, social, intellectual, academic, artistic, literary, moral or religious life, to which there might be ascribed the character of a true word of this kind. As distinct from Zwingli, who appealed to Hercules, Theseus, Socrates, Cicero and others, we have deliberately refrained from doing this.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[16]

So does Karl Barth affirm Natural Theology or not?

Nein! Nein! Nein! Barth does not affirm Natural Revelation nor any Natural Theology as follows! And Barth denies that his Secular Parables is engaging in the "the sorry hypothesis of so-called 'natural theology'". God is wholly other, and has only revealed himself in the threefold witness of the Word of God alone. Even if it were demonstrable that Barth's Secular Parables is indeed a Natural Theology, Barth denied that he was doing Natural Theology, and may be proved by CD IV/3.1, §69.2 The Light of Life:

we have no need to appeal either for basis or content to the sorry hypothesis of a so-called "natural theology" (i.e., a knowledge of God given in and with the natural force of reason or to be attained in its exercise). Even if this were theologically meaningful or practicable (which it is not), it could not provide us with what is required. By way of natural theology, apart from the Bible and the Church, there can be attained only abstract impartations concerning God's existence as the Supreme Being and Ruler of all things, and man's responsibility towards Him. But these are not what we have in view. What we have in view are attestations of the self-impartation of the God who acts as Father in the Son by the Holy Spirit, which show themselves to be such by their full agreement with the witness present in Scripture and accepted and proclaimed by the Church, and which can be material tested by and compared with this witness. What we have in view are words which like those of the Bible and the Church can be claimed as "parables of the kingdom."

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[17]

The Question of Science

Karl Barth is not an enemy of Science, and Barth's rejection of Natural Theology is not a rejection of science at all! See my Biologos article on Barth's affirmation of Creation, Science and Evolution. Some Evangelicals today attempt to juxtaposition the Bible against the Natural Sciences, in order to refute the established Scientific Consensus on various things such as Human Evolution because it disagrees with their hermeneutical approach to the Bible. Barth has no interest in any such endeavors and had no such thing in mind when he rejected Natural Theology! Barth lived in 20th century, post-WWII, war-torn Europe, and when he said No! (Nein!) to Natural Theology, he was opposing outside voices, such as the Nazis(!), whom wished to correct the Church's proclamation of Jesus Christ. Science is based on observing the natural world, so it is no threat to Christianity, because it will ultimately confirm Christianity as it observes Creation.

The Scientific Method requires observation of the empirical world, so if the universe did not exist, then there would be nothing to observe, ergo, no science! Barth believes that all mathematics and science are contingent on the existence of the world. Science does not precede the existence of the world, nor is it part of the world's origination (i.e. the event of Creation). Science is observation of the world as it exists according to the Scientific Method. Since, scientific laws are based on observations of the natural world, therefore all scientific laws, theories and hypotheses are contingent upon the existence of an observable cosmos. If the universe did not exist, then there would be nothing to observe in it, and therefore there would be no such thing as science as well.

These [natural and spiritual] laws are not the basis of existence. But with greater or lesser force, clarity and certainty they constantly show themselves to be the forms of its nature. It is not to them that existence owes its distinctive rhythm and contrariety. They can only confirm the constancy of both in relation to the constancy of their forms. They do not indicate the reality or substance but only the manner of the existence of the created world and the fact that it gives itself to be known and is known. They do not indicate the whole or totality of cosmic existence but only a part, i.e., the existence of creaturely being in certain specific sections and circles.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[18]

The natural laws are contingent upon the existence of the cosmos, and explain the existence of the cosmos in constancy, but they are secondary and therefore have no existence apart from creation. Barth said in CD III/1, that "Creation is the external basis of the Covenant, and the Covenant is the internal basis of Creation", but this does not mean that science or any natural laws are eternal, but it does mean that Science is an observation of Creation, and linked to it as a reflection of the Creation event. So this then means that the Word of God is the word of the Creator, and it is a word that precedes Creation and brings Creation to life. So the existence of the cosmos is contingent upon the word of God (Psalms 19), and does not depend upon it.

Laws are formulae for the relative necessity of certain objective and subjective processes and sequences. Such relative necessity of certain have already been disclosed and discovered, or will be. They are thus a fact, and with them the formulae. They cannot claim to be more than relative necessities because they relate only to limited spheres of existence, because even in these spheres the reality and substance of existence are presupposed and they can only describe its manner, and finally supremely because it is only in the encounter and converse between intelligible and intelligent cosmos that they can be valid, and this validity is limited and conditioned by the greater or lesser imperfection of the disclosure and discovery and revelation and establishment which take place in this encounter. It is only partially, formally, and above all within the world and the equivocal nature of all its relationships, that they are valid formulae. And it is only as valid in this way that they can claim to be constant and continual words and truths.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[19]

Science describes the ordinary happenings in nature, so it is may be true so far as it describes the world that materially agrees with the word of God. Science exists to confirm our understanding of the Created world.

They [natural laws] tell us nothing concerning God the Creator and Lord, nor concerning man in his relationship to God. For the Word of God, the revelation of the truth of God and man, is not pronounced by them. But again, this does not mean that we can ignore or despise them in their relative validity. Not all human knowledge, but an important part of it, namely, the so-called exact sciences built on empirical observation and investigation on the one side and mathematical logic on the other, are constituted in virtue of the knowability and in the knowledge of laws. We do not live only, but we do live also, by and with the facts that there are knowledge and technics in this sense, namely, that there are, as relative tenable and usable working hypotheses, these formulae which have partial and formal validity within the world as descriptions of relative necessities, and which really count, and may be counted upon, when they are defined in this way. If not according to "eternal," then certainly according to "brazen" and in their way "great" laws we must "all fulfill the circles of our being". We must and should. For in them we clearly have to do, if not with the light of God Himself, at least with lights of the world created by Him.

—Karl Barth, CD IV/3.1[20]

Although Barth was not opposed to Science or controversial theories such as Evolution, many desire that he had developed his Secular Parables further and expounded on places of intersection. Barth mentions Darwin and Darwinian Evolution only a few times in the entire Church Dogmatics. There is room here for more discussion, and Barth's Secular Parables is helpful to demonstrate that Barth's No! to Natural Theology is a Yes! to Science.

Conclusion

Karl Barth opposed Natural Theology until the end of his life. He believed that there is one and only one source for knowledge of God and that is only in God's self-Revelation through the threefold witness of the Word of God, namely in Jesus. Barth denied that there was any other knowledge of God apart from Jesus and he maintained this Nein! to Natural Theology until the end of his life.

Barth's protest against Natural Theology was also a protest against German Christians who wished to place Nazi propaganda besides the Bible as a second Bible of equal authority, and this is what Barth opposed in the Barmen Declaration. Long after the Nazis were defeated, Barth was free to revisit the question of Natural Theology without the fear of surrendering the gospel to the Nazis.

In the final volume of the Church Dogmatics (CD IV/3.1) Barth developed his own Natural Theology that he called "Secular Parables of the Kingdom". Although Barth appears to be backtracking on what he had said 25 years prior in his debates with Emil Brunner, he was not doing so, and remained consistently opposed to Natural Theology, however, now that the Nazis were removed from power, he was able to answer questions and add additional information to what he had written decades before due to relaxed political climate in post-World War II Germany.

Barth's Secular Parables is a Theology of Nature by Reflection. God may not be revealed in Nature, but God's revelation is reflected dimly in Nature, and there are places in Nature outside of God's self-Revelation that materially affirm what is apparent in God's self-Revelation, and these outside sources similar to parables, such that those who do not believe in God's self-Revelation are unable to understand them rightly, and they are lesser sources that may not correct what is revealed in God's self-Revelation.

Barth denied that it was the "so-called sorry hypothesis of Natural Theology", and he saw this doctrine as mutually exclusive from the traditional conception of theologia naturalis. Despite Barth's own assessment of the Secular Parables, it is possible to construe it as a Natural Theology, which is comparable to what Brunner had written in Nature and Grace (1934).

Recommended Reading

The fine folks at DET reminded me that George Hunsinger has a long appendix in his book on How to Read Karl Barth on "Secular Parables of the Truth". So if you wish to learn more about this superic from a trusty Barth scholar, I highly recommend this appendix for further reading.

References:

[^Header] By Tomruen (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

[^1] Barth, Karl, G. W. Bromiley, and Thomas F. Torrance. Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of God. Vol. II/1. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1975. 168. Print.

[^2] Ibid. 83. Print.

[^3] http://moltmanniac.com/karl-barths-letter-to-wolfhart-pannenberg/

[^4] https://postbarthian.com/2014/07/15/jurgen-moltmann-unfinished-summas-natural-theology/

[^5] https://postbarthian.com/2015/05/16/karl-barths-no-natural-revelation-faith-church/

[^6] See page for author [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

[^7] By NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (Flickr: New Moon) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

[^8] By Herrad von Landsberg - Hortus Deliciarum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31485263

[^9] Karl Barth, 1967, http://barth.ptsem.edu/uploadedfiles/bigsectionphotos/barth-1967.jpg

[^10] By Deutsche Bundespost - scanned by NobbiP, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11316278

[^11] By Hans Asper - Winterthur Kunstmuseum, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=553075

[^12] Barth, Karl, G. W. Bromiley, Thomas F. Torrance, and Frank McCombie. Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of Reconciliation. Vol. IV/4.3.1 Study Edition #27. London: T & T Clark, 2009. 127. Print. [133]

[^13] Ibid. 108. Print. [113]

[^14] Ibid. 107. Print. [112]

[^15] Ibid. 110. Print. [114-5]

[^16] Ibid. 129. Print. [135]

[^17] Ibid. 112. Print. [117]

[^18] Ibid. 139-40. Print. [146]

[^19] Ibid. 140. Print. [146-7]

[^20] Ibid. 140. Print. [146-7]

Related: barmen declaration, Emil Brunner, Jürgen Moltmann, Karl Barth, Natural Revelation, Natural Theology, Secular Parables, secular parables of the kingdom, secular parables of the truth

![Karl Barth (1967) [9]](https://postbarthian.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/barth-1967.jpg)

July 23rd, 2016 - 04:14

I agree with your assessment fully.

I would like to see what you think of this approach. If God exists, we must rely upon God to reveal who God is, on the analogy that if I am to let others know me, I must reveal myself to them. God has revealed who God is in Jesus Christ, revealing both the love and grace of God, the kindly disposition of God toward humanity. Such a revelation occurs in a “strange” way, given the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus. Yet, this strangeness is a sign of its revelatory character. It also shows our sinfulness and darkness. This is why we cannot look at ourselves or the world and arrive at a true knowledge of God. We can only acquaint ourselves thoroughly with the light of God in Christ. Our response to this revelation requires a turn toward it in recognition of it as the light of God in the world. We have faith or trust in this revelation. We give evidence of this faith by orienting our lives to that revelation. Here is where I depart from Barth, but I think Jesus would say such a life would reflect love of God and neighbor, Paul would say a life of faith, hope, and love, a life that reflects virtue and turns from vice, and even conduct within the household in a certain way. One of the things toward which I was looking forward in IV.4 was that Barth’s vision of the Christian life would be embraced by obedience in baptism and in the Lord’s Supper. In any case, as we orient our lives toward the true light that enlightens everyone, we can then see the lesser lights, the secular parables. We might find such parables in our families, places of work, communities, observance of nature, and so on. The interaction between the light of Christ and the light we find in human life and nature deepens our growth as disciples. – I actually wrote more than I intended. I understand if you do not have time. My reading recently in Barth, Bultmann, Pannenberg, and Congdon (whom I think you know), has been leading me to think through these matters a little differently.

July 23rd, 2016 - 06:25

From a linguistic standpoint, I believe that is is unfair to use the comparative function of a ‘parable’ against Barth since they can be multi-dimensional and operate at several levels of meaning at the same time according to modern literary models.Or to put it another way, there is no fixed principle that every ‘parable’ needs to state a single truth. Hence K.B. uses the plural number designing their many potential uses. Not that he agrees with every application. They have proper limitations as a teaching tool. In the case of Natural Theology this is especially true. Stating ‘as if'(ex hypothesi) is not the same thing as claiming some superior understanding.of a situation. gained by analogous experience; that inference “A’ must logically lead to the conclusion ‘B’. Nature itself does not necessary lead to a coherent.understanding of God.

August 20th, 2016 - 13:40

Recently, I was preparing for an Epiphany message next year. It struck me that all the magi had was what they saw in the sky. Those who had the revelation of God opposed what the magi interpreted as a sign from God that the Jewish Messiah had been born. Recognizing that this is Matthew’s theology, not history, it still makes me wonder. Could those who have these secular parables see God more clearly than those who have revelation? Then, I read this in Acts 10:34 “Then Peter began to speak to them: “I truly understand that God shows no partiality, 35 but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him.” It made me wonder if Luke does not provide an example of a secular parable here, where some human beings will “naturally” have a sense of awe regarding the divine and have a sense of what is “right.” At this point, I am not so much arguing with Barth, but thinking of ways to help him out biblically. The Bible may well point the way in which the people of God can have some humility in receiving such parables from outside the sphere of revelation.

I should also say that even Pannenberg would agree with the rejection of Natural theology as Barth describes it. The value of a modest form of Natural Theology is that it provides a bit of common ground from which one can share the revelation of God in Christ. It provides a touch point, I think David Congdon put it in his book on the Mission of Demythologizing.

August 20th, 2016 - 22:48

Barth says something similar about non-Christians in CD IV/3.1. He says that when a non-Christian denies Christ, he does not know what he is talking about or what he is saying. And then Barth goes on to say that Christians may live very un-Christlike and many non-Christians live more Christlike than some Christians. I’ve been planning to write on this topic soon.

That’s a fascinating tie to Natural Revelation, thanks for reading and commenting again!

Wyatt

October 3rd, 2016 - 09:51

Reading barth is like finding meaning in a pollack painting first barth only understands nature in context to his cranium. So for birth to say we can or cannot in context to nature is garbage of someone sitting around reading to many books. Religion and science in barthian fantasy reality hold nature to be subject subjective to it. Garbage. Reality, nature unto itself, is objective to the subject subjective observer the cranium. Christianity functions more as a book cult lost in outer space buy that’s called sin. I call it normal at the university level. Barth sounds like niels bohr and his fantasy interpretation of quantum mechanics where nature exists based on the observer. There is nothing in theology worth much and birth adds zero.

November 27th, 2018 - 18:04

Lyndia is the place I’m called but you can call me anything such as.

She is currently a hotel receptionist. His

wife and him living now in Idaho. Playing badminton is what his family and him enjoy. http://Andrew.Meyer@stacie.esposito@p.ro.to.t.ypezpx.h@ul.t.im.Ate.ly.h.Djr@m.n.E.m.on.i.c.s.x.wz@Okongwu.chisom@toyzhunt.com/node/6831/track

April 21st, 2020 - 01:23

An attitude like this would seem to necessitate a high view of scripture as being truly inspired and inerrant, as it is the only source of our knowledge of God. If you have a low view of scripture and you deny the possibility of understanding God through natural theology then what is left? It seems to be a position of implicit agnosticism. Barth may hold this position. I think his modern day followers who attack scripture as being errant, unreliable and pseudepigraphal cannot deny the reality of natural reality since if you can’t rely on scripture, nor can you discern anything of God through nature what are you left with?

Liberal Christians often place modern scientific and historical knowledge above scripture. A view such as Barths seems to act as a bulwark against this kind of relativistic shift where scripture is a set of ancient moral principles rather than inspired revelation from God.

July 30th, 2020 - 08:37

Thank you for your helpful comment.

May 4th, 2021 - 01:54

I am truly blessed and further Enlightened about the Barth and Brunner debate on natural Theology. I am in agreement with your assesent. I also see African Theology in my context as nothing but natural theology which I believe Barth would have also challenged. Stay blessed. Yours. Hassan Musa, from Nigeria