Is the Church both visible and invisible? Karl Barth says No! He said the Church is visible, so it is wrong to apply the idea of invisibility to the Church. Since the Reformation, the Church has been commonly proclaimed to be both visible and invisible, and sadly since then there has been an increasing emphasis on the invisibility Church over against the visibility of the Church. Barth recognized that the idea of an invisible Church devalued the Church entirely and silenced its preaching of the gospel. According to Barth, the Church has always been a public uproar by a visible group since the time of the Apostles, and a Church that is not visible, is not the Church!

Is the Church both visible and invisible? Karl Barth says No! He said the Church is visible, so it is wrong to apply the idea of invisibility to the Church. Since the Reformation, the Church has been commonly proclaimed to be both visible and invisible, and sadly since then there has been an increasing emphasis on the invisibility Church over against the visibility of the Church. Barth recognized that the idea of an invisible Church devalued the Church entirely and silenced its preaching of the gospel. According to Barth, the Church has always been a public uproar by a visible group since the time of the Apostles, and a Church that is not visible, is not the Church!

As a Christian in Nazi Germany, Barth understood that the Church must be a visible light in the world (Matt 5:14-16). Remember that Barth was largely responsible for the Barmen Declaration that was used by the Confessing Churches to publicly oppose German Christians and the Nazi party during World War II. In his 1946 Bonn University lectures in war torn Germany, he spoke this bold and famous denunciation of an invisible Church (printed in his Dogmatics in Outline):

By men assembling here and there in the Holy Spirit there arises here and there a visible Christian congregation. It is best not to apply the idea of invisibility to the Church; we are all inclined to slip away with that in the direction of a civitas platonica or some sort of Cloud-cuckooland, in which the Christians are united inwardly and invisibly, while the visible Church is devalued. In the Apostles' Creed it is not an invisible structure which is intended but a quite visible coming together, which originates with the twelve Apostles. The first congregation was a visible group, which caused a visible public uproar. If the Church has not this visibility, then it is not the Church. Of course each of these congregations has its problems, such as the congregation of Rome, of Jerusalem, etc. The New Testament never presents the Church apart from these problems. At once, the problem of variations in the individual congregation crops up, which may lead to splits. All this belongs to the visibility of the Church, which is the subject matter of the second article. [1]

The origin of the visible and invisible Church

The Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF) and other Reformed Confessions distinguished between the visible and invisible Church to communicate that mere membership to any ecclesiastical body does not guarantee salvation because after all justification is by faith alone! The visible vs. invisible Church distinction intended to communicate that there may be false Christians within the Church and many true Christians outside of the Church, or as St. Augustine said "there are many sheep without and many wolves within" (par. City of God). The WCF identifies the Pope as the Antichrist (WCF XXV.VI) as an example of a false Christian in the visible Church (n.b. many modern Churches that conscribe to the WCF have removed this condemnation of the Pope). And, the Protestants excommunicated during the Reformation would naturally be identified as true Christians that were not part of the only visible Church established in that time and place: i.e. the Roman Catholic Church.

"The . . . Church, which is invisible, consists of the whole number of the elect . . . The visible Church, which is . . . (not confined to one nation, as before under the law), consists of all those throughout the world that profess the true religion and of their children" (Westminster Confession of Faith, XXV.VI.I-II)

Thankfully, the stark antithesis between the Roman Catholics and Protestants in the 16th century, no longer exists today, but sadly the antithesis between the visible and invisible Church is starker than ever before. Unfortunately, the elevation of the invisible Church over the visible Church had the unintended and detrimental side effect of undermining the Church's visible presence in the world entirely, and reduced the visible Church to a private matter of individuals that had no public influence.

Separatists and fanatics capitalized on the visible and invisible Church distinction to identify their own sects with the invisible Church and then became vocal antagonists of the visible Church or anyone who did not share their fanatacial beliefs, as such was the case in the New Light vs Old Lights controversies in the Great Awakenings at the beginning of the 18th century in America where fanatical students frequently declared their Christian professors and leaders to be "unconverted". The idea of a visible and invisible Church had good intentions with the potential of showing great charity towards people outside the visible Church but in the end, the idea collapsed into pessimism and sectarianism and finally devaluation of the Church and the gospel.

The idea of a visible and invisible Church had good intentions with the potential of showing great charity towards people outside the visible Church but in the end, the idea collapsed into pessimism and sectarianism and finally devaluation of the Church and the gospel.

Four points against the Visible and Invisible Church

Karl Barth dismantles the Visible and Invisible Church taxonomy in the Church Dogmatics Vol III/4 with these four points: 1) The Church, according to Karl Barth, may not be identified with any nation, territory or country—this is Constantinianism. 2) Nor may the Church be identified with any establishment, institution or denomination whether Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox or otherwise. 3) The Church is not a means to some other end, it is the people of God in service of the coming kingdom. And 4a) the Church may not be divided into two groups of real vs unreal Christians, or useful vs useless Christians or true vs false Christians; and likewise 4b) nor may it be divided into the teaching class vs the listen class, or clergy vs laity.

Barth's Introduction to the Four Points

The following quotations form one continuous quotation from the Church Dogmatics III/4, that I've divided in order to review and comment on each paragraph:

When we put the service of the Christian community at the head of concretions of the active life demanded by the command of God, we make four assumptions which are certainly to be found in the New Testament but which unfortunately are not to be seen so clearly, and sometimes not at all, in what is operative and visible as the Christian Church of a particular tradition and confession. This is not the place for a detailed proof of these assumptions, and therefore we can only mention them in the present context. [2]

Barth's rejection of the visible and invisible Church isn't a return to Constantinian Christianity, where being a Christian meant being a member of a particular state, civilization or institution at a particular time and place. The Church is not bounded by time or geographical map lines, and extends from Jerusalem to the ends of the earth and ends of the ages (c.f. Matt 28:19-20). The Church is more visible than any civilization that man has ever devised.

We assume that the Christian community or Church is a particular people, and therefore that it neither is nor can be identical with humanity or with a natural or historical segment of humanity, as, for example, a nation or the population of a certain territory or country. We assume that it always represents a distinct antithesis to humanity as naturally and historically fashioned and to all the associated groupings. We thus assume that the numerical equation of Christianity, customary since the time of Constantine, with a supposed Christian West, rests on an error which, although it has not arisen without the permissive guidance of God and therefore to some purpose and profit, is still glaring and fatal, and can only result in the self-deception of the Christian community of Church and the hampering of its service.

Since its Lord is no other than the One who rules over heaven and earth, it is in fact a peculiar people, assembled and to be assembled from all nations, and existing in dispersion among all nations with its special task and service. It is constituted by the imminent kingdom of God and not by any kind of great or small historical dominion. It has not to look to even the highest interests either of humanity or of this or that greater or smaller human group, but in conflict with humanity and all human groups, and for their salvation, it must serve the particular interest which God in Jesus Christ both willed to take, and in His patience will always take, in humanity. It cannot try to be the Church of the people, but only the Church for the people. Only in this sense can it be the "national" Church. [3]

Barth is not dismissing Christian civilizations or any particular Church, but rather he is saying that the Church is visible in all these manifestations and yet not limited to them.

We assume that by the Christian community or Church is not meant an establishment or institution organised along specific lines, but the living people awakened and assembled by Jesus Christ as the Lord for the fulfillment of a specific task. In obedience to its Lord this people may and must provide itself with particular institutions, rules, regulations and obligations. But these do not constitute the Christian community; they are themselves made by the Christian community. They are always, it is to be hoped, the best possible and yet changeable forms in which the Christian community is active and undertakes to perform its service. The Christian community is active and undertakes to perform its service. The Christian community does not live as these institutions subsist and are maintained and protected. It lives as it discharges its service to the kingdom of God in the changing, standing and falling of institutions. What it has to do must not be determined by its institutions; its institutions must be determined by what it has to do. [4]

Barth does not believe that the Church is a means to some other ends, but it is a realization here and now of what is to come. In paganism, there's a dream of good times after death, such that we must endure the present trials of life in order to dine in the halls of Valhalla. We have already realized the coming kingdom of God, and this hope isn't wish-fulfillment but a present reality.

We assume that the Christian community or Church is in fact the people which has been constituted and given its commission by Jesus Christ its Lord and therefore by the coming kingdom. Its existence, therefore, is not an end in itself. Even the temporal and eternal reward which it has been promised for fulfilling its commission is something apart. It can and should look forward to this with gladness. But the meaning and purpose of its service do not consist in the receiving of it. Nor does it serve in order to satisfy its religious needs, to practice its piety, to live out its religious emotions, and thus to deepen and enrich its own life and possibly to improve or even transform world conditions. Nor does it serve in order to gain the favor of God and finally to attain to everlasting bliss. It serves because the causa Dei (cause of God) is present in Jesus Christ, and because, come what may and irrespective of the greatness or smallness of the result, it imperiously demands the service of its witness. [5]

a.) true and false members or b.) into the teachers and listeners

The fourth point may be the most important, and is divided into two sub-points:

We assume that the Christian community or Church is the people which as such is unitedly and therefore in all its members summoned to this service. Two common distinctions are herewith abolished. [6]

The first sub-point is that there are not two Church, a visible and invisible Church, but all belong to both the visible and invisible Church: the Church's membership is not divided into separate groups, but all Christians live under the severe warning that though they are visible, they may be invisible Christians in the end due to sin: it's both/and, instead of either/or.

a.) The first is the recognition, far too readily accepted as self-evident especially in many of the Reformation confessions, that the Christian community comprises many dead as well as living members, i.e., Christians only in appearance. The truth is that not merely some or many but all members of the Christian community stand under the sad possibility that they might not be real Christians, and yet that all and not merely some or many are called from death to life and therefore to the active life of service. It is quite impossible, and we have no authority from the New Testament, to admit into the concept of the Christian community a distinction between real and unreal, useful and useless members. That all are useless but that all are used as such is said to all who are gathered to this people. [7]

The second sub-point expresses a similar rejection of dualism in the Church; there are not two castes in the Church: the teaching and listening Christians.

b.) [The second is this] Again, the distinction is also abolished between a responsible part of the community specially called to the service of the Church and a much larger non-responsible part, i.e. between "clergy" and "laity", office bearers and ordinary Christians. The whole community and therefore all its members are specifically called to this service and are therefore responsible. All are mere "laity" in relation to their Lord, and therefore in truth, yet all are "clergy" in the same relation and therefore in truth. Admittedly, the service is inwardly ordered, so that there are within it different callings, gifts and commissions. Nevertheless, the community is not divided by this ordering into an active part and a passive, a teaching Church and a listening, Christians who have office and those who have not. Strictly, no one has an office; all can and should and may serve; none is ever "off duty." [8]

We may compress these four assumptions into the well-known words of 1 Pet 2:9f: "But yet are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who has called you out of darkness into his marvelous light: which in time past were not a people, but are now the people of God: which had not obtained mercy, but now have obtained mercy." We may immediately add to this saying the exposition and application of the threefold office of Jesus Christ given under Qu. 32 of the Heidelberg Catechism: "Why art thou called a Christian? Because through faith I am a member of Christ and partake of His anointing, that I may confess His name, offer myself to Him as a living sacrifice, and with a clear conscience wrestle in this life against sin and the devil, hereafter to reign with Him in eternity over all creatures." If only the Protestant conception of the Church had been worked out and practiced along these lines! [9]

Final Remarks on Universalism

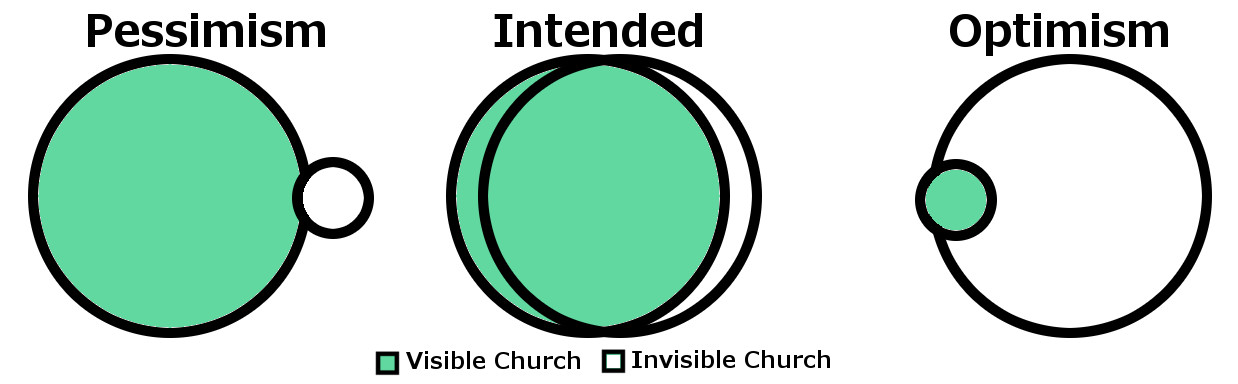

Barth's criticisms of the visible and invisible Church are primarily directed against those who define the invisible Church as smaller subset of the visible Church. However, this discussion precludes the hopeful possibility of the invisible Church having an exceedingly greater populous than the visible Church: e.g. the hope that all people would be included in the invisible Church. Such an affirmation of the invisible Church provides hope for universal salvation, but sadly it is most often used pessimistically to declare the true Church to be a small subset of true believers within the visible Church. The visible vs invisible church is a valuable taxonomy when the invisible church is believed to be a superset of the visible church, especially when the invisible church is optimistically identified as a universal set that includes all humanity or all Creation. If Barth's dismantling of the visible vs invisible church is affirmed, the door to universal salvation is still open, by allowing salvation to be extended to those outside the visible Church. Either way, we have hope that all people will be saved (1 Tim 2:4)!

References:

[^Header Image] Background church imaged is from Bernard Gagnon - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9029499

[^1] Barth, Karl. Dogmatics in Outline. New York: Harper & Row, 1959. 142. Print.

[^2] Barth, Karl. Church Dogmatics, Vol III/4. Study Edition 20. London: T & T Clark, 2010. 159. Print. Study Edition.

[^3] Ibid. 159, [488]

[^4] Ibid. 159-60, [488-9]

[^5] Ibid. 160, [489]

[^6] Ibid. 160-1, [489-90]

[^7] Ibid. 160-1, [489-90]

[^8] Ibid. 160-1, [489-90]

[^9] Ibid. 161, [490]

Related: Invisible Church, Karl Barth, Visible and Invisible Church, Visible Church

April 29th, 2016 - 08:01

Great post, PostBarthian!

I think Barth is absolutely right on this.

Thanks.

April 29th, 2016 - 10:54

Thanks Juan!

November 9th, 2022 - 13:33

I’m struggling with the visible church immensly, also, since I call myself a born again Christian and do hate to see mainline Churches, Anglican,Uniting Church ( all Australia ) allowing their bishops to marry man. How and where should I worship God, than in a homechurch with the bible in front !?