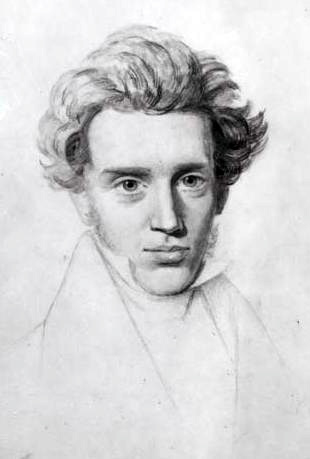

Practice in Christianity : Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 20, by Søren Kierkegaard (edited by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong) is the second philosophical-theological work that I've read by Kierkegaard. It was recommended by my Scholarly Friend, and I call him my "Scholarly Friend" because its only appropriate to use pseudonyms when engaging with Kierkegaard. I've read portions of Either/Or and Fear and Trembling but I'm most interested in Kierkegaard's specifically Christian works penned under the pseudonym of Anti-Climacus. Was 1849/1850 Kirkegaard's Annus Mirabilis (Miracle Year)? 1849/1850 was the year that Kierkegaard not only wrote Practiec in Christianity (aka Training in Christianity) but also Sickness Unto Death (See my last blog for more info).

Practice in Christianity : Kierkegaard's Writings, Vol 20, by Søren Kierkegaard (edited by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong) is the second philosophical-theological work that I've read by Kierkegaard. It was recommended by my Scholarly Friend, and I call him my "Scholarly Friend" because its only appropriate to use pseudonyms when engaging with Kierkegaard. I've read portions of Either/Or and Fear and Trembling but I'm most interested in Kierkegaard's specifically Christian works penned under the pseudonym of Anti-Climacus. Was 1849/1850 Kirkegaard's Annus Mirabilis (Miracle Year)? 1849/1850 was the year that Kierkegaard not only wrote Practiec in Christianity (aka Training in Christianity) but also Sickness Unto Death (See my last blog for more info).

Practice in Christianity is dominated by Kierkegaard's critique of Christendom, and his vexation with the Established Church of Denmark. Kierkegaard laments that "all a Christians in Christendom" and there is no understanding of suffering or offense because everyone in the country has been Christianized and baptized as Christians regardless of individual experience. In Theology, those Christians who have died are considered to be part of the "Church Triumphant" and Christians still living and awaiting the second coming of Christ on Earth are described as the "Church Militant." Kierkegaard complains that Christendom has turned the Church Militant into the Church Triumphant, and has commandeered the Eternal Heavenly state without it being realized. This is a major theme throughout Practice in Theology, and it is analogous to Dietrich Bonhoeffer's "Cheap Grace" vs. "Costly Grace" taxonomy.

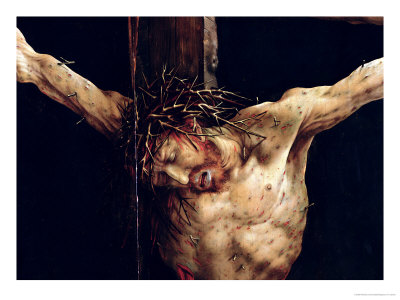

In response to Christendom, Kierkegaard develops a theology of offense and a way of suffering for Christians. Kierkegaard coins the term "Religious Narcissism" to describe Christians who see God as a divine source of help in their fight against the Devil. Kierkegaard laments that Religious Narcissism excludes the chastening that a Father must give to their children, and that the discipline of a Child is what identifies that Child with its Father. I read David J. Gouwen's "Kierkegaard as Religious Thinker" before Practice in Theology as a study aid to Kierkegaard. Gouwen's book was helpful as an overview of the philosophical and theological writings of Kierkegaard's complete works; and although it was not as helpful as Walter Lowrie's biography, A Short Life of Kierkegaard, in terms of understanding Kierkegaard, the Gouwen's book highlighted several selections by Kierkegaard. The following quotation helps understand Kierkegaard's understanding of Luther's Theology of the Cross, in a discussion about images that are familiar to children. Most images of people like Napoleon are glamorous figures on a high horse with feather capped uniforms and valiant posses, and how the images of the crucifixion are so entirely foreign to Children:

"[...] this picture, and will ask what it means, why he hangs like that on a tree. So you explain to the child that this is a cross, and that to hang on it means to be crucified, and that in that land crucifixion was not only the most painful death penalty but was also an ignominious mode of execution employed only for the grossest malefactors. What impression will that make upon the child? The child will be in a strange state of mind, it will surely wonder that it could occur to you to put such an ugly picture among all the other lovely ones, the picture of a gross malefactor among all these heroes and glorious figures. For just as a reproach to the Jews there was written above His cross, "The King of the Jews," so this picture, which regularly is published every year as a reproach to the human race, is a remembrance which the race never can and never should be rid of, it never should be represented differently; and it will seem as if it were this generation which crucified Him, as often as this generation for the first times shows this picture to the child of the new generation, explaining for the first time it hears this, will become anxious and sorrowful, for his parents, for the world, and for himself; and the other pictures--surely (as the ballad relates) they must turn their faces away, this picture being so different. However--and we have not yet reached the decisive point, the child has not learned who this gross malefactor was--with the curiosity children always have, the child will no doubt ask, "Who is it, what did he do? Tell me." Then tell the child that this crucified man is the Savior of the world. Yet to this he will not be able to attach any clear conceptions; so tell him merely that this crucified man was the most loving person that ever lived. Oh, in common intercourse, where everyone knows that story by rote as familiar patter, in common intercourse, where a half-word thrown out as a hint is enough to apprise everyone what is meant--there it goes so glibly; but verily it must be a wonderful man, or rather an inhuman one, who does not instinctively cast down his eyes and stand almost like a poor sinner the moment he must tell this to a child for the first time, to a child who has never heard a word about it before, and consequently has never surmised such a thing. But then at that moment the parent stands as an accuser, who accuses himself and the whole race!--What impression now do you think it will make upon the child, who naturally will ask, "But why were people so bad to him then?"

-- pg160, Søren Kierkegaard, Training in Christianity, (trans. Walter Lowrie).

Leave a comment