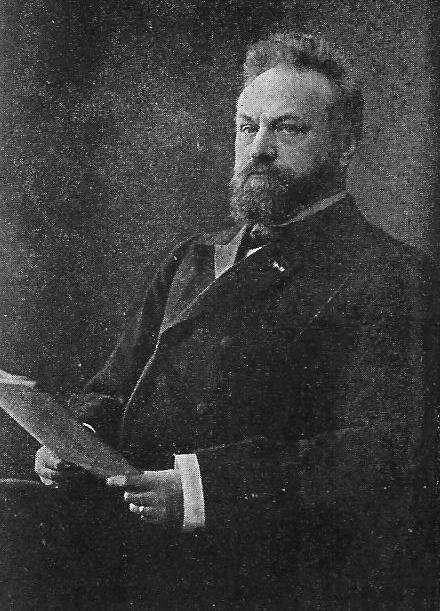

Herman Bavinck (source: rpcnacovenanter)

Herman Bavinck was a Dutch Calvinist who wrote an influential Reformed Dogmatics, and this is part two in my analysis of Bavinck's Doctrine of Inspiration of the Scriptures. As I previously shared, the Dutch Calvinists were not encumbered in fundamentalist debates over inerrancy like their American Calvinist counter-parts. Bavinck stayed closer to the spirit of the reformation, and especially to John Calvin, in his understanding of Inspiration of the Scriptures.

Bavinck developed his own "Organic Inspiration" theory in contrast to what he called the "Fundamentalist" or "Mechanical Inspiration" known today as Inerrancy, which was a trap that perceived that even the Reformed confessions had fallen into, a trap that his own Organic Inspiration theory had evaded.

The Reformed confessions almost all have an article on Scripture and clearly express its divine authority; and all the Reformed theologians without exception take the same position. Occasionally one can discern a feeble attempt at developing a more organic view of Scripture. Inspiration did not always consist in [new] revelation but, when it concerned familiar matters, it consisted in assistance and direction. The authors were not always passive but also time active.

Bavinck, Herman. Reformed Dogmatics: Prolegomena. Ed. John Bolt. Trans. John Vriend. Vol. 1. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011. 414. Print.

Bavinck wrote, the "'fundamental' approach to inspiration is in conflict with this dogmatic and religious character of the doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture." (pg 436) and "Erring in the other direction are those who favor a mechanical inspiration, thereby failing to do justice to the activity of the secondary authors." (pg430) Bavinck believed that the Scriptures did not contain errors so far as they communicated the "history of salvation", and although the truth of Scriptures in this regard extended positively to all spheres of life [in true Kuyperian fashion!], yet this precision did not extend to scientific and historical detail. Bavinck does not affirm that the Scriptures contains errors, but when faced with errors in the realms of geology, zoology, physiology, medicine, or other areas of science and history, Bavinck concludes that it was not the intention of the Scriptures to answer those details positively that it could be invoked to adjudicate between world-views such as the Ptolemaic versus the Copernican systems. It is only the error of Mechanical and Fundamentalist theories of inspiration that stretched the Scriptures beyond the truths they communicate regarding salvation that are forced to reconcile the errors created by these deficient systems.

Bavinck's Organic Theory of Inspiration was further developed by G.C. Berkower, which I will discuss in the future, and although Bavinck lacks some of the developments that were to come later from Dutch Calvinism, he is still in a healthier vein of the Reformed Church on this topic. An example of this is how Bavinck remained open to Higher Criticism and appreciative of Schleiermacher in a way that old Princeton never was, and he maintained an helpful distinction between the Revelation and Inspiration of the Scriptures, as the following quotations will demonstrate.

I've collected the following selections from Bavinck's Reformed Dogmatics: Prolegomena Vol.1 Only recently has the entire four volume Reformed Dogmatics been translated into English.

On Schleiermacher and Revelation vs Inspiration:

Revelation and inspiration are distinct; the former is rather a work of the Son, the Logos, the latter a work of the Holy Spirit. There is therefore truth in Schleiermacher's idea that the holy authors were subject to the influences of the holy circle in which they lived. Revelation and inspiration have to be distinguished.

Ibid. 426

On the a-historical character of the Gospels and Pentateuch, the lost original autographs, and the advantages of Higher Criticism:

Holy Scripture has a purpose that is religious-ethical through and through. It is not designed to be a manual for the various sciences. [...] Historical criticism has utterly forgotten this purpose of Scripture. It tries to produce a history of the people, religion, and literature of Israel and a priori confronts Scripture with demands it cannot fulfill. It runs into contradictions that cannot be resolved, endless sorts out sources and books, rearranges and reorders hem, with only hopeless confusion as the end result. No life of Jesus can be written from the four Gospels, nor can a history of Israel be construed from the OT. That was not what the Holy Spirit had in mind. Inspiration was evidently not a matter of drawing up material with notarial precision. "If indeed the four gospels words are put in Jesus' mouth with reference to the same occasion but dissimilar in the form of their expression, Jesus naturally could not have used four different forms; but the Holy Spirit only aimed to bring about for the church an impression which completely corresponds to what came forth from Jesus." (Abraham Kuyper, Encyclopedia, II, 499).

Scripture does not satisfy the demand for exact knowledge in the way we demand it in mathematics, astronomy, chemistry, etc. This is a standard that may not be applied to it. For that reason, moreover, the autographa were lost; for that reason the text--to whatever small degree this is the case--is corrupt; for that reason the church, and truly not just the layman, has the Bible only in defective and fallible translations. These are undeniable facts. And these facts teach us that Scripture has a criterion of its own, requires an interpretation of its own, and has a purpose and intention of its own. That intention is no other than that it should make us "wise unto salvation." The Old Testament, while not a source for the history of Israel's people and religion, is such a source for the history of revelation. The Gospels, while not a source for a life of Jesus, are such a source for a theological (dogmatic) knowledge of his person and work. The Bible is the book for Christian religion and Christian theology. To that end it has been given, and for that purpose it is appropriate. And for that reason it is the word of God given us by the Holy Spirit.

Ibid. 444-5

And,

There are intellectual problems (cruces) in Scripture that cannot be ignored and that will probably never be resolved.

Ibid. 442

On how the Scriptures do not reveal science:

[Cardinal] Baronius' saying: "Scripture does not tell us how the heavens move but how we move to heaven."

[...] there is also a large truth in the saying of Cardinal Baronius. All those facts in Scripture are not communicated in isolation and for their own sake but with a theological aim, namely, that we should know God unto salvation. Scripture never intentionally concerns itself with science as such. [...] But for that very reason too it [Scripture] is not a scientific book in the strict sense. Wisdom, not learning, speaks in it. It does not speak the exact language of science and the academy but the language of observation and daily life. It judges and describes things, not in terms of the results of scientific investigation, but in terms of intuition, the initial lively impression that the phenomena make on people.

For that reason it speaks of "land approaching," of the sun "rising" and "standing still," of blood as the "soul" of an animal, of the kidneys as the seat of sensations, of the heart as the source of thoughts, etc. and is not the least bit worried about the scientifically exact language of astronomy, physiology, etc. It speaks of the earth as the center of God's creation and does not take sides between the Ptolemaic and the Copernican world-view. It does not take a position on Neptunism versus Plutonism, on allopathy versus homeopathy. It is probable that the authors of Scripture knew no more than all their contemporaries about these sciences, geology, zoology, physiology, medicine, etc. Nor was it necessary. For Holy Scripture uses the language of everyday experience, which is and remains always true. If, instead of this, Scripture had used the language of the academy and spoken with scientific precision, it would have stood in the way of its own authority. If it had decided in favor of the Ptolemaic worldview, it would not have been credible in an age that supported the Copernican system. Nor could it have been a book for life, for humanity. But now it speaks in ordinary human language, language that is intelligible to the most simple person, fear to the learned and unlearned alike. It employs the language of observation, which will always continue to exist alongside that of science and the academy. In recent times a similar idea has been articulated by many Roman Catholic theologians with respect to the historiography found in Scripture.

Ibid. 445-6

On Higher Criticism and Demythologizing the New Testament:

Yet it is true that the historiography of Holy Scripture has a character of its own. Its purpose is not to tell us precisely all that has happened in times past with the human race and with Israel but to relate to us the history of God's revelation. Scripture only tells us what is associated with that history and aims by it to reveal God to us in his search for and coming to humanity. Sacred history is religious history. [...] Considered from the viewpoint and by the standards of secular history, Scripture is often incomplete, full of gaps and certainly not written by the rules of contemporary historical criticism. [...] In its determination of time and place, in the order of events, in the grouping of circumstances, it certainly does not give us the degree of exactness we might frequently wish for. The reports about the main events, say, the time of Jesus' birth, the duration of his public activity, the words he spoke at the institution of the Lord's Supper, his resurrection, etc., are far from homogeneous and leave room for a variety of views.

Ibid. 447

On how literal theories of the inspiration makes the bible impossible:

Whether the rich man and the poor Lazarus are fictitious characters or historical persons is an open question. Similarly we can differ about whether and in how far we must regard the book of Job, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon as history or as historical fiction. This is especially clear in the case of prophecy. The Old Testament prophets picture the future in colors derived from their own environments and thereby in each case confront us with the question of whether what they write is intended realistically or symbolically. Even in the case of historical reports, there is sometimes a distinction between the fact that has occurred and the form in which it is presented. In connection with Genesis 1:3 the Authorized Version [Dutch] comments in the margin that God's speech is his will, his command, his act, and in connection with Genesis 11:5 that this is said of the infinite and all-knowing God in a human way. This last comment, however, applies to the whole bible. It always speaks of the highest and holiest things, of eternal in invisible matters, in a human way. Like Christ, it does not consider anything human alien to itself. It is old without ever becoming obsolete. It always remains young and fresh; it is the word of life. The word of God endures forever.

Ibid. 448

On the Testimony of the Holy Spirit is superior to Dictation:

Inspiration alone would not yet make a writing into the word of God in a Scriptural sense. Even if a book on geography, say, was inspired from cover to cover and was literally dictated word-for-word, it would still not be "God-breathed" and "God breathing" in the sense of 2 Timothy 3:16. Scripture is the word of God because the Holy Spirit testifies in it concerning Christ, because it has the Word-made-flesh as its matter and content.

Ibid. 443

Against Mechanical Inspiration theories:

A mechanical notion of revelation one-sidedly emphasizes the new, the supernatural element that is present in the inspiration, and disregards its connection with the old, the natural. This detaches the Bible writers from their personality, as it were, and lifts them out of the history of their time. In the end it allows them to function only as mindless, inanimate instruments in the hand of the Holy Spirit. To what extent theologians in the past held to such a mechanical view cannot be said in a single sweeping statement and would have to be explored separately in each individual case. It is true that the church fathers already started comparing the prophets and apostles, in the process of writing, with a cipher, a lyre, a flute, or a pen in the hand of the Holy Spirit. But we dare not draw too many conclusions from these comparisons. In using these similes they only wanted to indicate that the Bible writers were the secondary authors and that God was the primary author. This is evident from the fact that, on the other hand, they firmly and unanimously rejected the error of the Montanists, who claimed that prophecy and inspiration rendered their mouthpieces unconscious, and often clearly recognized the self-activity of the biblical authors as well. Stile, from time to time, one encounters expression and contradictions that insight into the historical and psychological mediation of revelation--now taken in a favorable sense--only came to full clarity in modern times and that the mechanical view of inspiration, to the extent that it existed in the past, has increasingly made way for the organic.

Ibid. 431

July 1st, 2020 - 21:11

You might be interested in an article I wrote on this in the context of the Rogers-McKim vs Gaffin controversy –

‘Upholding Sola Scriptura Today: Some Unturned Stones in Herman Bavinck’s Doctrine of Inspiration’ International Journal of Systematic Theology 20/4 (2018).

September 18th, 2020 - 14:05

Usually insurance will protect you from the most common accidents

however, many companies require you to pay a supplementary fee per type of

disaster that could occur. One kind of asset finance is where a

firm commits for an Operating Lease. With it you cannot only start or off the “bolt on benefit” feature but in addition avoid the surrender charge.