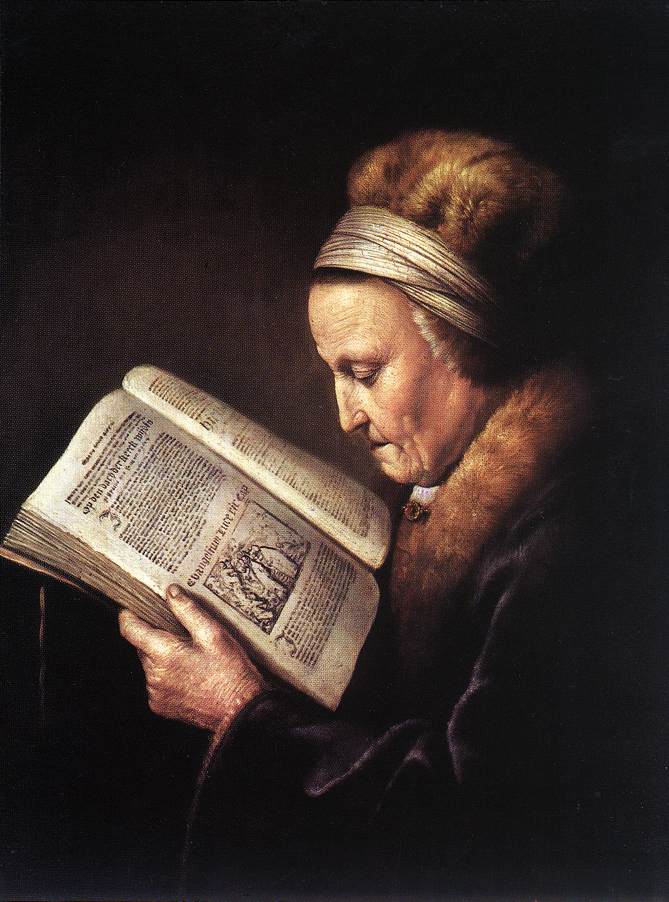

Gerard Dou (source:wikipedia)

Jack Rogers and Donald McKim's historical analysis of the Doctrine of the Inspiration of Scriptures, The Authority and Inspiration of the Bible (AIB), created a firestorm in the late 1970's due its conclusion that the Reformers' Doctrine of Inspiration (exemplified by John Calvin and the Westminster Confession of Faith) was abandoned by Protestant Scholasticism (exemplified by Francis Turretin and John Owen) and Old Princeton (exemplified by Charles Hodge, B.B. Warfield and A.A. Hodge) who replaced it with a mechanical view of inspiration that was foreign to the Reformers. This departure by Turretin and Old Princeton became firmly established in Evangelicalism until today, a grievous example is the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy. [See my previous articles on Calvin's use of Accommodation and Calvin's allowance for errors in the autographs for examples of how Luther and Calvin would not affirm Inerrancy.]

The Reformers emphasized faith seeking understanding as they approached the Bible, and expected to learn from it how to become wise unto salvation, and that they believed that the bible used accommodation to reveal truth that didn't require absolute precision in every factual detail, such that we possessed the Inspired Word of God in the manuscripts that we now possess, and not in the lost and non-existing original autographs! Turretin and Old Princeton inverted this approach to scripture and elevated reason over faith in their hermeneutic and stretched the meaning of the inspiration of the Scriptures to extreme ends, such that the very words were mechanically inspired and that the very words (ipsissima verba) were absolutely precise in every scientific detail of all areas of knowledge, and at the climax of mechanical inspiration's development, this precision was extended to even the Hebrew vowel pointers of the Masoretic Text and included an assertion that the inerrant original autographs were still extent in the 17th century despite some variants in various known copies before these claims became scientifically indefensible, such that a subsequent retreat to the non-existing original autographs entailed to defend their novel and unassailable tautology.

The Authority and Interpretation of the Bible is a survey of the history of the Doctrine of Inspiration from birth of Christianity until today. It contains an excellent assessment of Plato and Aristotle and their influence on the Christian tradition of this loci of scripture, and it contains an overview of the principle contributors to the development of the Doctrine of Inspiration. The book is particularly valuable to Presbyterians who cherish the reformed tradition, John Calvin, and the Westminister Confession of Faith. AIB is not a 'turn back the clock' book because it includes an excellent appendix on G.C. Berkouwer and Karl Barth as examples of better approaches of solutions to understanding scripture that have developed in the Reformed Church tradition.

The publication of Authority and Inspiration of the Bible caused a firestorm of criticism during the Battle for the Bible, and generated endless books and articles "refuting" the Rogers/McKim Proposal. Rather than responding to any of them, I will share some quotations from the "Rogers/McKim Proposal" to encourage Evangelicals to read this excellent book!

This first quote summarizes the problem that Francis Turretin introduced:

A century after Calvin's death, the chair of theology in Geneva was occupied by Francis Turretin (1632-1687). In that interval of one hundred years Reformed Protestants had reacted to Catholic criticism and the new science, and the reigning theological method was closer to that of a Counter-Reformation interpretation of Thomas Aquinas than to that of Calvin. A doctrine of Scripture that made the Bible a formal principal rather than a living witness had been gradually developed. Turretin further solidified this shift of emphasis from the content to the form of words of Scripture as the source of its authority. He treated the forms of words of Scripture as supernatural and increasingly divorced the text of the Bible from the attention of scholarship and an application to life.

In the generation immediately following Francis Turretin in Geneva, his son, Jean-Alphonse Turretin (1648-1737) led a revolt against scholastic theology that opened the doors to liberalism. Francis Turretin's theology was to be revived, however, and have its greatest influence in America during the era of the old Princeton theology in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At Princeton, further refinements were made in the scholastic doctrine of Scripture, but the foundation had been solidly laid by Turretin.

Rogers, Jack Bartlett., and Donald K. McKim. The Authority and Interpretation of the Bible: An Historical Approach. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1979. 172. Print.

The following quotation explains John Calvin's Concept of Error in the Inspired Scriptures:

For Calvin, technical errors in the Bible that were the result of human slips of memory, limited knowledge, or the use of texts for different purposes than the original were all part of the normal human means of communication. They did not call into question the divine character of Scripture's message. Nor did they hinder the completely adequate communication of God's Word. In fact, they enhanced the telling of the Good News because they were part of God's gracious accommodation of himself to human means and thus made the message more persuasive to human beings. Scholars could and should deal openly and honestly with technical problems according to Calvin's theory and his own practice. Calvin would not allow, however, that a biblical writer had ever deliberately lied, or knowingly told an untruth. Error in the moral and ethical realm was far removed from the biblical writers.

Ibid. 111

Just as Calvin did not expect the Bible to be a repository of technically accurate information on language or history, neither did he expect that the biblical data should be used to question the findings of science. Calvin did not feel that the Bible's teaching had to be harmonized with science. The purpose of Scripture was to bring persons into a right relationship with God and their fellow creatures. Science was in another sphere and was to be judged by its own criteria. In his commentary on Genesis 1:14-16, Calvin faced the issue of the relationship of the Bible to the science of his day. The problem to some people was that the moon was spoken of in the Bible being one of the two great lights, with the starts being mentioned only incidentally. Astronomers of Calvin's day had proved that Saturn, because of its great distance from earth appeared to be a lesser light than the moon, but was really a greater light.

Ibid. 111-2

AIB provides a powerful argument that the appeal to the original autographs became a primary tenant to Inerrancy because it was no longer possible to state the science supported Inerrancy. Charles Hodge believed that science supported mechanical inspiration, but A.A. Hodge lead the retreat to the inerrant original autograph tautology:

Despite the intended uniformity of thought among the Princeton theologians, significant changes were made in successive generations. Archibald Alexander began with religious experience and used reason and evidence to confirm it. Charles Hodge continued to honor religious experience as a valid basis for personal religion. He preferred the internal evidence the Bible presented to the reader over external evidences of its authority. But in the classroom and in writing Hodge asserted that theology was a science and stressed objective proofs of the Bible's divinity. By the time of his son, A. A. Hodge, the sciences were no longer supporting Princeton theories of biblical inerrancy. A. A. Hodge rested his case on external evidences, but shifted the object of inerrancy to the original (lost) autographs of the biblical text.

Ibid. 310

I learned that the Dutch Calvinists were not consumed by the Turretin/old-Princeton aberration, and had remained far more faithful to Calvin and the Reformers of accommodation. I've explored Herman Bavinck's analysis of Inspiration in his Reformed Dogmatics and his personal view of organic inspiration.

Together, [Abraham] Kuyper and [Herman] Bavinck perpetuated a theological method which, particularly with regard to Scripture, followed the line of Augustine and the Reformers rather than that of the post-Reformation scholasticism preferred by the Princeton theology. The Dutch Reformed tradition held to the Augustinian method that faith leads to understanding rather than the medieval scholastic view that reasons were necessary prior to faith. Thus, the primary issue for the Dutch Reformed tradition was the functional one of how God related to humankind rather than the philosophical issue of whether God's existence could be proved. In relation to the Bible, that meant the Holy Spirit moved persons to accept Scripture as authoritative because of the saving message it expressed rather than that human reason compelled persons to believe the Bible because of evidential or logical proofs of its divine character.

Ibid. 389

June 22nd, 2016 - 14:02

It’s amazing one can actually write such a groundless delusion long ago refuted by Dr. Woodbridge:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0310447518

No wonder Jesus, God’s Word Incarnate, tells us how He hides His things from the alleged “wise and understanding” and reveals them unto babes: Matthew 11:25; Luke 10:21. Soli Deo gloria!

It’s fascinating to see those like Dr. Woodbridge (e.g. Dr. Walter Kaiser & the late Dr. Gleason Archer) who really know what these old scholars actually taught shred these absurd “tower of babble” notions above that don’t begin to pass the smell test. Conveniently not one verse of God’s Word is cited since 2 Timothy 2 orthotomounta would expose the fraud. God always has he last laugh,

Psalm 2.

Soli Deo gloria!

June 22nd, 2016 - 14:43

Hello Russ, thank you for reading my blog post on the Rogers and McKim proposal. I’m aware of Woodbridge’s book in response. Simply writing a book in response, is not the same thing as refuting. Ground breaking discoveries are always following by people who wish to refute that very same discovery. Inerrancy places strict rules on what the “God breathed word” may and may not say. If God has revealed himself in a way contrary to Inerrancy says, then Inerrancy is idolatry. Inerrancy is a deep misunderstanding about the Bible that Jesus opposed, such as in John 5:39-40. “You search the scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that testify on my behalf. Yet you refuse to come to me to have life.”

Wyatt

August 14th, 2019 - 20:17

Woodbridge put Rogers and McKim’s claims to bed. He showed clear evidence that the chiasm they sought to “expose” between Calvin / Scholastics / Princeton was poor historical scholarship at best and purposefully misleading at worst.

Argue all you like for a liberal view of scripture’s authority, but don’t try to rewrite history to support your innovation.

August 19th, 2019 - 21:14

Jono,

I am well acquainted with Woodbridge’s book. Will you please cite a specific Rogers and McKim claim that it refutes and the corresponding page in Woodbridge’s book? Publishing a book that repeats the same old errors, is not a refutation. On the contrary, such books as Woodbridge’s is consistent with the slavish loyalty to an antiquated view of scriptures.

If you’d like to avoid “poor historical scholarship” then please do not engage in it yourself.

Wyatt