In Part 1: Burned Alive at the Stake of this Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr series, I described the horrific execution of Michael Servetus. In Part 2, I will explain that John Calvin is guilty for the death of Michael Servetus, but this guilt is shared by the Geneva Council, the Protestant Church, the Catholic Church, and the whole world of the 16th century.

Michael Servetus versus the World

"For many, the execution of Michael Servetus in Geneva has defined John Calvin's posthumous reputation." [1] John Calvin is to be blamed for Michael Servetus' execution (as I will discuss later) but it is a mistake to blame Calvin alone. "After the execution Calvin sought, and received such universal approval from all over the world for what had been done in Geneva, even to the burning (of which he himself disapproved) that it was obvious that the world of his day felt it could not allow such a radical fanatic the least opportunity to conduct a militant crusade for his views." [2] At the time, everyone of note who was consulted approved of the deed. "Servetus suffered the fate that hundreds of heretics and Anabaptists suffered at the hands of Protestant authorities of all shades of opinions, as well as Catholic authorities" [3]. Servetus was well known and was detested in many places besides Geneva." [4] Servetus had provoked Calvin but he had also provoked the whole world, and the whole world had colluded against him—Protestant and Catholic alike.

John Calvin's Guilt

John Calvin is responsible for Servetus death, and Henry Beveridge explains why Calvin is guilty for the death of Servetus in a famous footnote of his translation of the Institutes of the Christian Religion:

"He [John Calvin] asked the councils of Geneva to arrest the heretic Michael Servetus, brought charges against him, carried on the debate to prove that his heresy was threatening the Church of Christ, and approved of the verdict to put him to death (although he urged beheading instead of burning at the stake). Calvin even wrote a small book defending the death sentence upon Servetus." [5]

It is very unlikely that Servetus would have died without Calvin, but Calvin did not act alone, nor upon his authority alone. Calvin shared the same conviction as the whole world, that it was necessary to put heretics to death who injured the church, state or anyone therein. François Wendel explains in his book Calvin: Origins and Development of His Religious Thought that:

"Calvin was convinced, and all the reformers shared this conviction, that it was the duty of a Christian magistrate to put to death blasphemers who kill the soul, just as they punish murderers who kill the body." [6]

Servetus died, in large part due to Calvin's belief that the church and state must be protected from heretics, and Calvin did everything within his power and under legal due process to oppose a notorious heretic. Calvin was a magisterial reformer, and before Servetus was executed, Calvin wrote in his institutes that it was not the role of the church to use the sword against heretics, but the world at that time approved of putting heretics and Anabaptists to death frequently.

In a later installment of this series, I'll discuss how Calvin departed from his earlier theology (such as his 1543 Latin edition of his Institutes of the Christian Religion) that limited the punishment of heretics to excommunication alone, and discuss how Calvin in the post-Servetus period argued that the magistrate (or state) had the divine right to punish heretics, even to the point of executing them.

John Calvin is guilty of an error of his age, and for not following his own theology, when he advocated for the wrongful death of Michael Servetus in 1553.

Geneva's Guilt

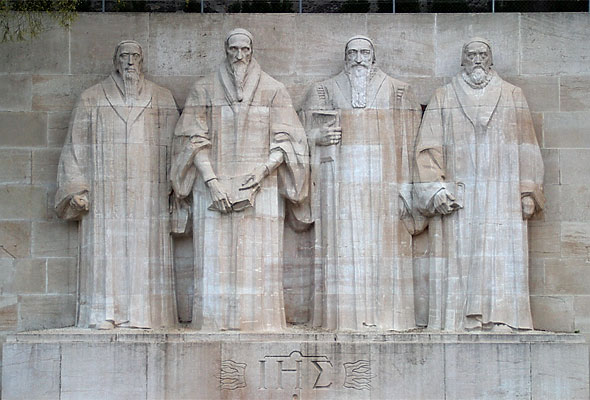

Reformation Wall in Geneva: Farel, Calvin, Beza, and Knox

It is difficult to imagine the execution of Servetus happening in the same way without John Calvin, however Servetus had already escaped execution once before, and had received condemning statements from many theologians besides John Calvin. So it is likely that Michael Servetus would have ended up executed as a heretic somewhere somehow.

It's important to state again that Servetus was arrested, tried, condemned and executed by the Genevan Council—not John Calvin individually or upon Calvin's order or authority alone. Servetus had quarreled with Calvin for decades before he arrived in Geneva, and had been condemned by other reformers, and had escaped execution early in that same year of 1553 by the Catholic Church and French authorities. So Servetus' reputation as a "notorious heretic" preceded him to Geneva.

Theodore Beza reports in his biography of Calvin that "upon his arrival in Geneva, Servetus was recognized by several who had come across him elsewhere" [7] and others including William Farel (a.k.a. Guillaume Farel) participated in the prosecution of Servetus too, Calvin did not act alone. No doubt, Servetus was arrested, tried and executed due to his decades of arguing with Calvin leading up to his arrival in Geneva, but Servetus was reckless in advocating his anti-Chalcedonian and anti-Nicene theology, and that made the world a dangerous place for Servetus no matter where he went.

An important fact, that demonstrates that the Geneva Council acted on its own volition and was not Calvin's puppet is demonstrated by the Genevan Council's choice to use a more severe and inhumane form of execution than Calvin desired; this shows that Calvin did not authoritatively orchestrate the events of the execution, even though he made significant contributions that caused them to happen. Arguably all the citizens of Geneva demanded the death of Servetus for his crimes of heresy.

It was the Genevan Council that executed Michael Servetus, and although John Calvin advocated for this action, it was the Genevan Council who was most guilty for Servetus' death.

The Protestant Church's Guilt

All the leading protestant representatives outside of Geneva approved of the execution of Servetus too. Before condemning Servetus, the Genevan Council sent letters to the other Swiss city-states for a second opinion on Servetus (demonstrating further that Servetus was not put to death based upon Calvin's opinions alone) and they all praised the Genevan Council's death sentence for Servetus: "Zurich, Bern, Basel, and Schaffhausen were asked to pronounce on it. . . . there seems to have been a unanimous judgment against Servetus, with some rare exceptions" [8]. Calvin also sent many letters to justify his involvement in the execution of Servetus, and the responses he received also demonstrate that the Genevan Council was the most responsible for Servetus' death as well. I will share some example responses from famous theologians outside of Geneva (or who came to Geneva later), that show that the execution of Servetus was approved by the entire Protestant Church at that time.

Heinrich Bullinger, the famous Swiss Reformer and successor of Ulrich Zwingli in Zurich approved of the execution of Michael Servetus and wrote to Calvin: "God has given you an opportunity to wash us all clean from the suspicion of being heretics or favoring heresy if you show yourselves vigilant and ready to prevent this poison from spreading further" [9] and Cottret said that "Bullinger condemned Servetus as a demon from hell and wrote to Calvin that the Genevan church had been given a glorious opportunity to strike against heresy."

Notably, Martin Luther's famous successor and Lutheran leader "Philip Melanchthon wrote to Calvin, 'I have read your answer to the blasphemies of Servetus and approve of your piety and opinions. I judged also that the Genevan Senate acted correctly to put an end to this obstinate man, who could never cease blaspheming." [10]

Theodore Beza, Calvin's successor in Geneva (who came to Geneva after Servetus was executed), viewed Servetus as a sub-human monster and said "This Spaniard [Servetus] of cursed memory was not so much a man as a monstrous embodiment of all the heresies, old as well as new . . . he was condemned on 27 October to be burnt at the stake as the righteous judgment of God and men on his crimes." [11] The entire Protestant world applauded the Genevan Council's decision to burn Servetus at the stake for failing their arcane religious tests.

John Calvin was not the first to condemn Michael Servetus. Servetus had received condemnations for his theologians long before he was executed. Servetus had clashed with famous theologians and churches arguably before he first encountered Calvin. As early as the 1530's, Martin Bucer and Johannes Oecolampadius encountered Servetus and made similar condemnations of Servetus: "Oecolampadius, who at last took offense at this ideas [i.e. Servetus' theology] . . . Oecolampadius summoned Servetus, if he still wanted to be considered a Christian, to recognize Jesus as the Son of God, consubstantial with the Father." [12] And, "Bucer publicly refuted this work, and it was banned, in Strasbourg as well as in Basel." Bucer said Servetus "was worthy of having his entrails torn out" [13] and this was not an idle threat.

The Catholic Church's Guilt

The entire Protestant church applauded the execution of Michael Servetus, and the Catholic Church applauded it as well—the whole world opposed Servetus, the "notorious heretic." Not long before Servetus was executed in Geneva in 1553, the Catholic Church had imprisoned him in Vienne after John Calvin had given the French authorities a tip about the "notorious heretic in their midst" [14] but Servetus managed to "escape over the rooftops on April 7. He was condemned in absentia on June 17. The sentence was executed by burning him in effigy along with five bales of blank paper, used to represent his works" [15] in Paris.

Bernard Cottret suggests that John Calvin and the Genevan Church used Servetus as a pawn, in a move to regain "entrance into the communion of the saints" [16] by aiding and abetting the Roman Catholic Church's arrest of Michael Servetus. Calvin and the Genevans may have taken advantage of Servetus to secure an alliance or truce with the Roman Catholic Church, and neither the Geneva Church or the Catholic Church had any real care or concern for Servetus. Cottret summarizes frankly that they believed that "A good heretic is a dead heretic. Calvin's conduct can also be explained, more prosaically, by his fear of a popish plot aimed at destabilizing his position in Geneva . . . Servetus was treated by both sides as a . . . double agent that neither camp recognized as . . . their own." [17] Cottret summarizes Calvin's argument in a syllogism based on a lost letter: "Socrates is a man, and therefore mortal; Servetus is a heretic, and therefore combustible." [18] Cottret also cites a "terrible sentence" [19] from a lost letter from John Calvin on Servetus that says: "One should not be content with simply killing such people, but should burn them cruelly." [20]

Michael Servetus was condemned by the Whole World

The sixteenth century post-Reformation period was not a time of religious freedom or free speech. It was an era when the fledgling Protestant church fought for survival, and this resulted in wars between churches and states grounded in religious differences. Churches regularly anathematized each other. A person with "orthodox" beliefs in one church or state, was considered "heterodox" in other churches or states, and moving from place to place was a life endangering maneuver. Servetus was a martyr because he died for having different theological beliefs, and asking questions that were forbidden. Servetus died as a martyr for Christians who were wrongly executed for not conforming to the theological hegemony of the church and state in the place where they lived. The whole world condemned Servetus, and therefore he must be remembered as a martyr, so that we remember not to execute those who believe differently than us.

In Part 3 I will discuss the origin of Michael Servetus' radical theology.

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 1: Burned Alive at the Stake)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 2: A Person Condemned by the Whole World)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic and Martyr (Part 3: A Radical Theology)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic and Martyr (Part 4: A Twenty Year Fight to the Death with John Calvin)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 5: A Defense of John Calvin and the Calvinists)

Sources

1. Bruce Gordon, Calvin, Yale University Press: 2009, Great Britton, Print. p. 217

2. Ronald S. Wallace, Calvin, Geneva and the Reformation: A Study of Calvin as Social Reformer, Churchman, Pastor and Theologian, Wipf & Stock Publishers: 1998, Eugene. Print. p. 77.

3. François Wendel, Calvin: Origins and Development of His Religious Thought, Harper & Row, 1950, Print. p. 97.

4. Ronald Wallace. Ibid. p. 74

5. Henry Beveridge, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1850. Print. IV.xx.16, footnote 587

6. François Wendel. Ibid. p. 97

7. Theodore Beza, The Life of Calvin: A Short Biography of John Calvin, Print. p. 63

8. Bernard Cottret, Calvin: A Biography, T & T Clark: 2000, Grand Rapids. Print. p. 224.

9. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 220-1

10. Bruce Gordon. Ibid. p. 224.

11. Theodore Beza. Ibid. p. 63

12. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 214-5

13. Ronald Wallace. Ibid. p. 74

14. Bruce Gordon. Ibid. p. 218.

15. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 223.

16. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 221.

17. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 221.

18. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 222.

19. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 222.

20. Bernard Cottret. Ibid. p. 222.

21. Header contains Image: "Michael Servetus in prison, by Clotilde Roch. Monument in Annemasse, France" (source: wikipedia)

22. Image of Martin Bucer (source: wikipedia)

23. Image of Theodore Beza (source: wikipedia)

24. Image of Philip Melanchton (source: wikipedia)

25. Image of John Calvin (source: wikipedia)

26. Image of Henry Bullinger (source: wikipedia).

27. Image of William Farel (Guillaume Farel) (source: wikipedia).

Related: Bernard Cottret, Bruce Gordon, Catholic Church, Geneva, Geneva Council, Guillaume Farel, Heinrich Bullinger, John Calvin, Martin Bucer, Martin Luther, Michael Servetus, Philip Melanchthon, Servetus, ServetusSeries, Theodore Beza, William Farel

Leave a comment