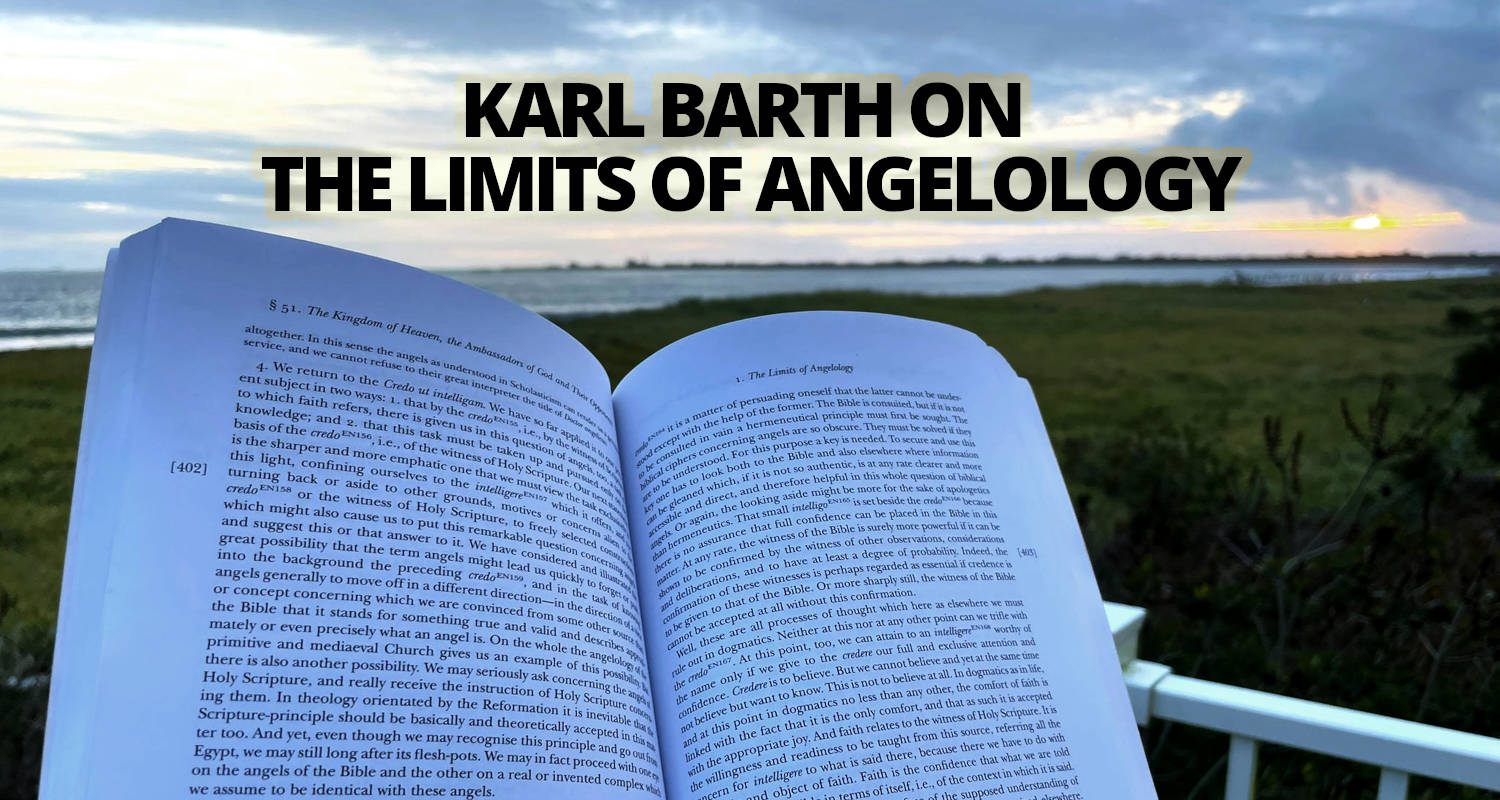

What truth may we speak about angels? It is a daunting theological locus. Of angels, Karl Barth says “How are we to steer a way between this Scylla and Charybdis, between the far too interesting mythology of the ancients and the far too uninteresting ‘demythologization’ of most of the moderns?” [1]. I often err to be an uninterested demythologizer, especially when I am in conversation with others who are far too interested in angels. The good news is that Karl Barth has written an excellent paragraph on "The Limits of Angelology" (§51.1) in the Church Dogmatics Vol. III/3 that I will summarize in this article as a path through the rock and a hard place of angelology.

History of Angelology

Karl Barth's "The Limits of Angelology" (CD III/3 §51.1) is a test case of Barth's hermeneutical method that he uses throughout the Church Dogmatics. Barth begins his doctrine of angels by tracing through the development of angelology throughout church history, identifying key individual contributors and developments—critiquing them along the way—and ultimately returning to exegete the witness of the scriptures to reconstruct his own angelology anew.

In "The Limits of Angelology", Karl Barth identifies many positive and negative contributors to the doctrine of angels that are worth mentioning (especially Origen), but for the sake of brevity, I will focus on the two most significant people: Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Thomas Aquinas. Barth says that Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and Thomas of Aquinas are “the great climax in the history of angelology” [2]. Two quotes summarize Barth's opinion of these two titans of angelology. Of Pseudo-Dionysius, Karl Barth said, “We have here the work of one of the greatest frauds in Church History” [3]. (As to why? I will leave it as an exercise for the reader.) Of Thomas Aquinas, Barth said with a large grin “It was probably because of this series” on angelology in the Summa Theologica in which “No less than 118 individual questions are raised and answered by Thomas on this theme” that “earned the particular title in the Middle Ages of Doctor Angelicus.” [4]. Barth credits Origen for devising the idea that all people have a guardian angel “with the dubious addition that we all have a bad angel as well” [5], and thus historical development has the good angel of Thomas sitting on one shoulder and the bad angel of Pseudo-Dionysius perched upon the other. Ultimately, Barth brushes off both angels from the shoulders before returning afresh to the biblical witness of scripture.

Thomas Aquinas's Angelology

Karl Barth ultimately rejected Thomas Aquinas' angelology because it was founded upon philosophical arguments rather than the biblical witness, and no church doctrines should be based solely upon natural revelation.

Barth disagreed with Thomas' method but he deeply admired Thomas' achievement in angelology. Barth spills most of his ink in this paragraph on Thomas, and praises Thomas many times but he could not resist many backhanded compliments. For instance, Karl Barth said of Thomas Aquinas “This work of probably the greatest angelogue of all Church history, unfortunately, has nothing whatever to do with the knowledge of the veritas catholicae fidei [the truth of the Catholic faith]” [6] (the subtitle of Thomas’ Summa Contra Gentiles)

Barth provides an eight-point summary of Thomas' proofs for the existence of angels as noncorporeal distinct substances (e.g. spiritual creatures) that is worthwhile to summarize, especially since it is useful to use this eight-point list to contrast Thomas from Barth's own angelology:

1. The survival of the human soul after the dissolution of the body in death

2. A human subsists in a soul/body dichotomy, and the separation of the intellectual substance has existence in the human creature along, QED other creatures may exist with intellectual substance without bodies.

3. From lesser to the greater, the existence of primitive animals without a soul, and the chain of animals with increasing degrees of intellectual substances up to humans means at the far developed end a creature that is purely intellectual substance may exist

4. Variant imperfections of the body also restrict the perfection of the soul, there a being with a perfected soul may be bodiless

5. A body has quantity of substances, but not all substances have quantity. QED substances exist without quantity (eg god). Creation was created perfect, thus it must contain bodiless substances.

6. If A human is an imperfect composite of individual intellectual and bodily substances, therefore a higher being must exist that the intellectual substance is without bodily substance.

7. A human beings intellectual substance (soul) may know things sensorily via the body, therefore there must be creatures who know the world directly in itself without the need of a body.

8. Pace Aristotle and the ptolemaic cosmology, there must be many unmoved movers. A human has a body so it cannot be a unmoved mover. [7]

*n.b. The above 8pt. list has been abridged for brevity and shareability.

Karl Barth says that Thomas believed that through this eightfold demonstration that he had refuted the Sadducees per Acts 23:8, as well as the ancient scientists that denied the existence of spirits, and the great Origen who believed God alone is non-corporeal being. Barth praises Thomas in many ways and respects his achievement in angelology. Nevertheless, Karl Barth concludes that evangelicals must not follow Thomas’ angelology because we must stand upon the human witness of scriptures, and not upon these eight logical proofs or any other argument from natural revelation. (I foresee many chagrin Thomists protesting this conclusion). Barth remained firm in this assessment and said that “As evangelical theologians, committed to the witness of the Bible, we are ill-advised to treat the subject on the ground which he was not the first to select but which he did so with a radicalness that can hardly be surpassed. And because we cannot do this, we cannot follow him in the detailed questions which he poses or answers which he gives.” [8]

Protestant Angelologies After Thomas Aquinas

Karl Barth had little respect for the Protestant rationalistic angelologies developed after Thomas in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. Of them Barth made this damning statement:

“In its misguidedness, we can compare it only with the foolish explanations which many modern theologians have given for their complete skepticism or indifference to the whole problem. And we must add that the negations of the moderns are explicable if not excusable against the background of the assertions of the ancients as classically codified and systematized by Thomas. Even the angelological views of Protestant orthodoxy have nothing to offer in the last resort except Thomas weakened and modified.” [9]

Barth provided another helpful eight-point summary of these later Protestant angelologies that demonstrates that they all depended on a similar presupposition birthed out of arguments based upon natural revelations, such there "must" be angels according to their philosophical proofs (like Thomas but worse). Barth chides these "must" arguments and says they are at best "rationes probabiles" (probable arguments) [10].

1. "The angels as inhabitants of the other heavenly bodies (Reinhard)."

2. "The angels as moral and spiritual individuals in the invisible kingdom of reason within the universe (Bretschneider)."

3. "The angels as the spirits of preceding spheres of creation perfected after undergoing a kind of angelic course (Rothe)."

4. "The angels as stimulators of spiritual life at the beginning of the human race (Dorner)."

5. "The angels as identical with intellectual forces and mythical deities (Martensen)."

6. "The angels as supreme and final products of the creative activity of God (Schlatter)."

7. "And finally, if the unexplained reference is really to angels, the angels as the members of a “plurality of spiritual realms” (Troeltsch)."

8. "Quamvis suaderi potest rationibus probabilibus. So far as one can be persuaded by probable arguments." (J. W. Baier) [11]

In response to these eight individuals, Karl Barth remarks: "Do I need to prove that it was all a mere groping in the dark, and that only the hazy pictures of a scattered and uncertain knowledge, only artificialities and platitudes, can result when the attempt is made, as in the case of angels, to learn from other sources as well as from the Bible?" More so, "Is it not plain that at this point philosophy has been corrupted by theology, not to speak of the corruption of theology by philosophy?" Behind this eight-point list is a unified and unspoken attack on Rudolf Bultmann, who is intentionally left unnamed to deny him any credibility. Barth concludes that later Protestant angelology has not improved upon Thomas Aquinas with these naturalistic philosophical arguments: "Everything leads into the void, and by comparison, the doctrine of angels taught by Thomas appears respectable." [12]

Back to the Scriptures!

After Barth finishes his critique of the history of angelic dogma, he returns to the scriptures (ad fontes) to reconstruct his own angelology utilizing the pro et contr of his historical analysis as to the human witness of scripture: Exegete! Exegete! Exegete! Barth says that we may not look to the bible and any other source because "if we try to find angels in the Bible and elsewhere, we shall only see hazy pictures.” [13] and “To look in two directions is not to see straight in either” [14] Consequently, “In the matters of angels it is better to look resolutely and exclusively in a different direction than to try to look at the Bible and other sources of knowledge at one and the same time.” [15]

An Angelic Conclusion

At last, we have finished surveying Karl Barth's negative criticism of angelologies that preceded him and begin to hear Barth's own angelology. Barth has shown that any angelology based on the Bible and any other source has consistently fallen into error and gross imagination throughout history. Barth is not a pure biblicist because he limits angelology to that witnessed in the scriptures; Barth uses his own hermeneutic and his knowledge of wrong turns in the historical development of angelology to guide us into an angelology within proper limits.

The mission of "The Limits of Angelology" (CD III/3, §51.1) has been apophatic, namely to identify what should not be done. The second section of Barth's angelology "The Kingdom of Heaven" (CD III/3, §51.2) is a cataphatic discussion of what may positively be said about the existence of angels that I'm planning to discuss in an upcoming post. In the meantime, I have already discussed the last part (three of three) of Barth's angelology by summarizing Barth's demonology §51.3 in my previous post, Karl Barth: Believing in Demons makes us Demonic.

I recommend the "Limits of Angelology" to anyone who wishes to know what may be positively or negatively be said about angels. And for fun, here's a famous quote attributed to Karl Barth:

"When the Angels sing for God, they play Bach, but when they sing for themselves they play Mozart, and God eavesdrops." —Karl Barth

Sources:

1. Barth, Karl. Doctrine of Creation III/3 §50-51. Study Edition ed. Vol. 18. London: T & T Clark, 2010. 79. [369]. Print. Church Dogmatics. (n.b. The first-page number refers to the study edition and the [square bracket page number] refers to the original pagination.)

2. Barth. Ibid. 101. [390]

3. Barth. Ibid. 96. [385].

4. Barth. Ibid. 112. [400].

5. Barth. Ibid. 94. [383].

6. Barth. Ibid. 102. [391].

7. Barth. Ibid. 102-4. [392-3]. (n.b. Quotations are abridged selections from this small print and may be imprecise quotes.)

8. Barth. Ibid. 112. [400]. (n.b. Quotations are abridged selections from this small print and may be imprecise quotes.)

9. Barth. Ibid. 102. [391-2].

10. Barth. Ibid. 112. [409].

11. Barth. Ibid. 121-2. [409].

12. Barth. Ibid. 112. [409-411].

13. Barth. Ibid. 116. [404].

14. Barth. Ibid. 116. [403].

15. Barth. Ibid. 116. [403-4]

Related: Adolf Schlatter, ambassadors of god, angel, angelology, angels, Bretschneider, CD III/3, Demons, Dorner, J. W. Baier, Karl Barth, Limits of Angelology, Martensen, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, Reinhard, Rothe, St. Dionysius the Areopagite, Thomas Aquinas, Thomist, Troeltsch

September 28th, 2022 - 13:24

Thank you for this helpful summary of the first part of Barth’s angelology. I look forward to your discussion of the second part. I also read your post on Pannenberg’s angelology. Thank you for offering such short, readable insights into the thoughts if these thinkers.

I am still left with the question why some angels are named in Scripture (Michael, Gabriel). This seems to give them a degree of personal identity. How would you respond to that based on your reading of Barth, Pannenberg and others?

I have been reading Tolkien’s Silmarillion and while I appreciate that this work draws from wells of mythology rather than Scripture, there is a profound expression of the free will of the nonhuman creation there, of which we also find echoes in the Bible. Could it be that Barth and Pannenberg make too little of this under the influence of modernist skepticism?