Is God a "She"? Jürgen Moltmann thinks so! Moltmann believes the Holy Spirit should be referred to with feminine attributes and names, such as "she" or "her" or "mother". This may be alarming to some evangelicals today, especially those use gender-inclusive languages for the purpose of scrubbing feminism out of the bible (compare the translation of Romans 16:7 in the ESV to the NRSV). Divine Femininity appears frequently in the bible and in Church History: The apostles describe themselves as "nursing mothers" (1 Thess 2:7) and God himself as well (Isa 49:15), and Jesus also in a maternal reference to Jerusalem like a mother hen (Matt 23:37). A simple search of the Bible reveals that the Divine Femininity appears frequently!

Is God a "She"? Jürgen Moltmann thinks so! Moltmann believes the Holy Spirit should be referred to with feminine attributes and names, such as "she" or "her" or "mother". This may be alarming to some evangelicals today, especially those use gender-inclusive languages for the purpose of scrubbing feminism out of the bible (compare the translation of Romans 16:7 in the ESV to the NRSV). Divine Femininity appears frequently in the bible and in Church History: The apostles describe themselves as "nursing mothers" (1 Thess 2:7) and God himself as well (Isa 49:15), and Jesus also in a maternal reference to Jerusalem like a mother hen (Matt 23:37). A simple search of the Bible reveals that the Divine Femininity appears frequently!

In the following quotation from Moltmann's The Spirit of Life: A Universal Affirmation, several examples of feminine and maternal images of God are discussed in a polemic explaining why Moltmann believes that the Holy Spirit should be "termed a 'feminine' Spirit." Moltmann's famous for his Social Doctrine of the Trinity, that sees the three persons of the one god as a society, emphasizing the three over the one, and the Divine Femininity brings the Trinity closer to the analogy of a nuclear family, such that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are familial understood as the Father, Mother and Son. "In Trinitarian theology, the image of the divine family raises the Spirit to the same rank as the Father, and puts the Spirit before the Son."

Understanding the Holy Spirit as a feminine Spirit brings Feuerbach's criticism of the Divine Family as a projection of the human family, that Moltmann begins to address below but requires more discussion. Additionally, does this Divine Femininity open the door to an affirmation of Mariology as exemplified by Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy?

Even if these two questions produce new problems, the strength of Moltmann's position is that his overthrows Trinitarian Patriarchy. Moltmann sides with the Eastern Orthodox's rejection of the filioque, because the Filioque subjugaftes the Holy Spirit to the Son, where in the East, the Son and the Spirit are two hands of Father as Irenaeus imagined. In Moltmann's view, the Holy Spirit is not subjugated to the Son or the Father, because the Holy Spirit appears besides the Father as the Divine Mother of the Divine Family, such that the Father and the Holy Spirit (as Mother) exclude both Patriarchy and Matriarchy. Both the Father and the Mother are hence liberated, and they are liberated in the Son (Jesus Christ), such that the Son (Jesus Christ) also is not subjugated to the Father or Mother (Holy Spirit).

If these experiences are thought of as rebirth or as being born again, this suggests a singular image for the Holy Spirit, an image which was quite familiar in the early centuries of Christianity, especially in Syria, but which came to be lost in the patriarchal Roman empire: the image of the mother. If believers are 'born' again from the Holy Spirit, then the Spirit is 'the mother' of God's children and can in this sense also be termed a 'feminine' Spirit. If the Holy Spirit is 'the Comforter' (Paraclete), it comforts 'as a mother comforts'. In this sense it is the motherly comforter of believers. Linguistically this again brings out the characteristics of the Hebrew expression 'Yahweh's ruach'.

The earliest testimonies are probably to be found in the Gospel of Thomas: 'He who will not love his Father and his Mother as I do, cannot be my disciple. For my mother gave me life.' In Jerome we find a quotation from a Hebrew gospel: 'When the Lord came up out of the water, the whole wellspring of the Holy Spirit came down and rested on him, and said to him: "My Son, in all the prophets I awaited thy coming, so that I might rest in thee. For thou are my rest, thou my first-born Son, who reigneth in eternity."' The Hebrew gospel has passed down the following saying: 'Then my mother, the Holy Spirit, seized me by the hair and bore me away to the great Mount Tabor.' In the Christian-Gnostic 'Hymn of the Pearl' (in the apocryphal Acts of Thomas), the Trinity consists of God the Father, the Holy Spirit as Mother, and the Son. In the Syrian version of the poem we find the prayers: 'Come merciful Mother' and 'Come, giver of life'. The Holy Spirit is also addressed as 'Mother of all created being'. In the Greek translations of these Gnostic text, 'Mother' is then often already replaced by 'Holy Spirit'.

Right down to Irenaeus, there was a struggle in the mainstream church against the Gnostic-Christian congregations, and this opposition also extended to feminine images of God, especially in the Roman empire. But among the Syrian Fathers this language held its ground. Aphraates is an early witness. In order to justify his problematical ascetic and celibate way of life, he said: 'Why does a man forsake father and mother when he takes a wife? This is the explanation: as long as a man has no wife, he loves and reverences God his Father and the Holy Spirit his Mother, and has no other love. But when the man has taken a wife, he leaves this Father and Mother of his, and his heart is fettered by this world.' The typically semitic, motherly form of the Holy Spirit can also be found in his view of the Paraclete.

The famous Fifty Homilies of Makarios the mystic come from the sphere of Syrian Christianity, and they inspired and influenced both the Orthodox churches and the churches of the West. The real author was in fact the theologian Symeon of Mesopotamia, who was a Messalian, not the desert father Makarios. These homilies talk about 'the motherly ministry of the Holy Spirit', using two arguments. 1. The promised Comforter (the Paraclete) will 'comfort you as a mother comfort's (here John 14:26 is put together with Isa 66:13); and 2. Only the person who has been 'born anew' can see the kingdom of God. Men and women are 'born anew' from the Spirit. They are 'children of the Spirit' and the Spirit is their 'Mother'. These homilies were translated into German in the seventeenth century by Gottfried Arnold, and were widely read in the early years of Pietism. John Wesley was fascinated by 'Macarios the Egyptians', and August Hermann Francke gave extensive treatment to 'the motherly ministry of the Holy Spirit' in his treatise on nature and grace. For Count Zizendorf, this perception was a kind of revelation, and in 1741, when the Moravian Brethren founded their community in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, he officially proclaimed 'the motherly office of the Holy Spirit'. In 1744 this finding was elevated to the rank of community doctrine.

By doing this, Zizendorf made the divine Trinity, conceived according to the pattern of a family, the prototype for the community of brothers and sisters on earth: 'since the Father of our LOrd JEsus Christ is our true Father, and the Spirit of JEsus Christ is our true Mother; because the Son of the living God . . . is our true Brother.' 'The Father must love us and can do no other, the Son, our brother, must love souls as His own soul, and must love the body as His own body, because we are flesh we are flesh of His flesh, bone of His bone, and He can do no other.' The biblical grounds Zinzendorf contributes was inspired by the era of 'sensibility' - the cultivation of the feelings - which was now beginning. What is motherly about the operations of the Spirit can be sensed in its tenderness and sympathy: '. . . they are driven forward by a certain tender Impulse, through Delight in the matter, through a blessed Attraction which souls feel for this and that thing, through a Sympathy which they also discover in themselves, and yet the awareness of the Savior and his Image is the concept. Paul Gerhardt describes the leadings of the Spirit in much the same way as a guiding 'with motherly hand' ('Mit Mutterhänden leitet er die Seinen ständig hin und her . . .').

The metaphor of rebirth or new birth makes it seem natural to talk about an engendering Deity. Here God is experienced, not as the liberation Lord but as 'the well of life'. Giving birth, nourishing, protecting and consoling, love's empathy and sympathy: these are then the expressions which suggest themselves as a way of describing the relations of the Spirit to her children. They express mutual intimacy, not sovereign and awful distance.

In Trinitarian theology, the image of the divine family raises the Spirit to the same rank as the Father, and puts the Spirit before the Son. Unless, like Ludwig Feuerbach, we wish to cast the image aside altogether as a pure projection of a family idyll, it does offer interesting corrective possibilities, if we compare it with the other pictures of the Trinity - Irenaeus's image of the One God with two hands, for example.

But more important than these speculative possibilities is the new definition of what it means for human beings to be the image of God. If the Trinity is a community, then what corresponds to it is the true human community of men and women. A certain de-patriarchalization of the picture of God results in a de-patriarchalization of the church too.

Of course by calling God the Holy Spirit 'Mother' we are merely putting parallel to the 'Father' another power as primal source. Psychologically speaking, inward liberation from the mother is as much a part of human development as emancipation from the Father. Like Israel's prophets, Christianity actually replaced the patriachal and matriarchal powers of origin by the messianism of the Child, as the bearer of hope and the beginning of the future. 'Unless you become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven' (Matt 18:3). But this is not brought out by the patriarchal or matriarchal image of God.

Moltmann, Jürgen. The Spirit of Life: A Universal Affirmation. Trans. Margaret Kohl. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993. 157-60. Print.

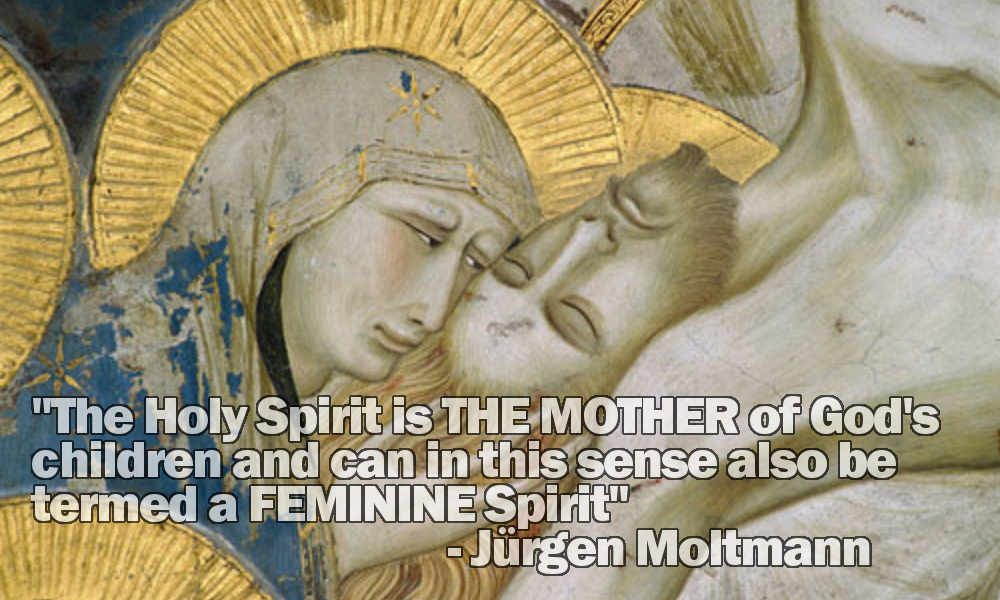

Header Image Source: "Pietro lorenzetti, compianto (dettaglio) basilica inferiore di assisi (1310-1329)". Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Related: Divine Family, feminism, Holy Spirit, Jürgen Moltmann, Social Doctrine of the Trinity, The Spirit of Life: An Universal Affirmation

May 18th, 2016 - 23:28

Lovely.

May 18th, 2016 - 23:31

Thanks again Kate for following!

July 20th, 2016 - 07:25

Very helpfull! I am amazed how this truth is not generally accepted in the Church. We need this truth to heal our hearts from the lack of tenderness and warmth we lack in this world. Thanks for sharing!

July 20th, 2016 - 07:38

I’m glad you appreciated it!