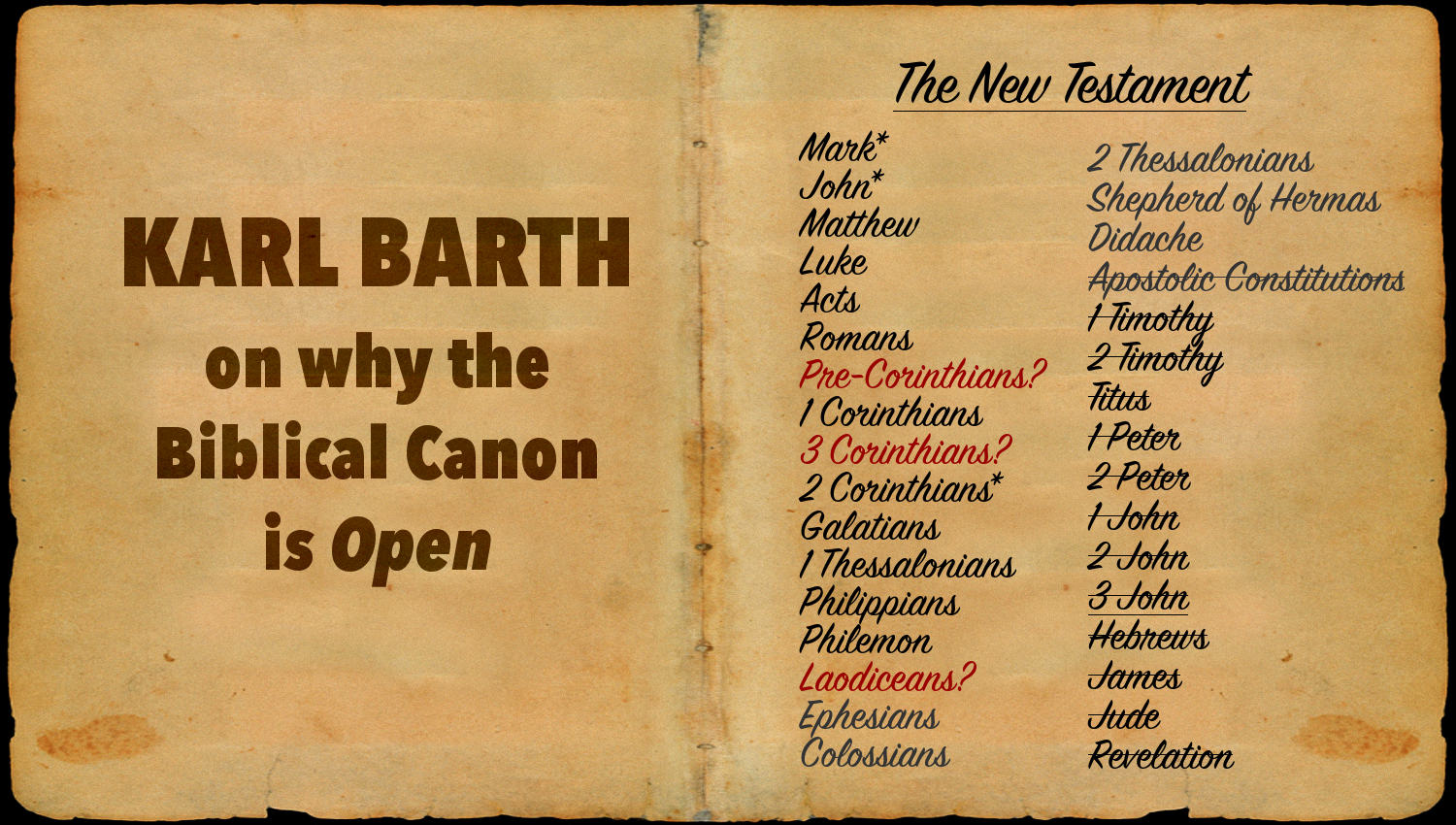

Karl Barth believed that the biblical canon is "very relatively closed", and yet it is still open to radical change in the future! Let me explain by analogy to a volcano that remains dormant for centuries, but then suddenly erupts, changing the landscape forever; likewise with the biblical canon, it has remained relatively closed for centuries, but at any unexpected moment, it may burst open again and suddenly be radically changed. For instance, Barth says that if one of the lost known letters of Paul were to be discovered in the sands of Egypt, then this apocalyptic revelation may break open the canon once again, causing new books to be added, and possibly existing books to be cast out.

Karl Barth believed that the biblical canon is "very relatively closed", and yet it is still open to radical change in the future! Let me explain by analogy to a volcano that remains dormant for centuries, but then suddenly erupts, changing the landscape forever; likewise with the biblical canon, it has remained relatively closed for centuries, but at any unexpected moment, it may burst open again and suddenly be radically changed. For instance, Barth says that if one of the lost known letters of Paul were to be discovered in the sands of Egypt, then this apocalyptic revelation may break open the canon once again, causing new books to be added, and possibly existing books to be cast out.

Perhaps Karl Barth's most famous statement on the openness of the biblical canon is as follows:

Karl Barth writes, "we recognize certain Scriptures (e.g., the sixty-six of our Authorized Version) to be canonical in and with the Church . . . An absolute guarantee that the history of the Canon is closed, and therefore that what we know as the Canon is also closed, cannot be given either by the Church or by individuals in the Church . . . In the past there has already been more than one proposal to narrow or broaden the human perception of what ought to count as canonical Scripture, and if the proposals never came to anything they were at least seriously considered. The insight that the concrete form of the Canon is not closed absolutely, but only very relatively, cannot be denied even with a view to the future." [1]

Three times when the biblical canon was re-opened

Barth described three distinct epochs when the biblical canon was open for addition and revision as follows:

Even if we ignore the considerable variations in the first four centuries, it is worth noting that the Council of Florence in 1441—a thousand years after our present-day New Testament had gained general acceptance—for the purpose of the understanding which was then sought with the Eastern Churches, could still think it necessary to put out an express list of the Old and New Testament writings recognized to be canonical (Denz. No. 706). This act had to be repeated in 1546 by the Council of Trent (Sess. IV Denz. No. 784), the problem of the Canon having meanwhile been reopened by the Reformation. The Protestant Churches—the Reformed very definitely, and at bottom too the Lutheran quite decidedly—thought it right to exclude from the Canon as “Apocrypha” a whole series of Old Testament writings which had been recognized as wholly canonical for a thousand years (the books of Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Tobias, Sirach and the two Maccabees).[2]

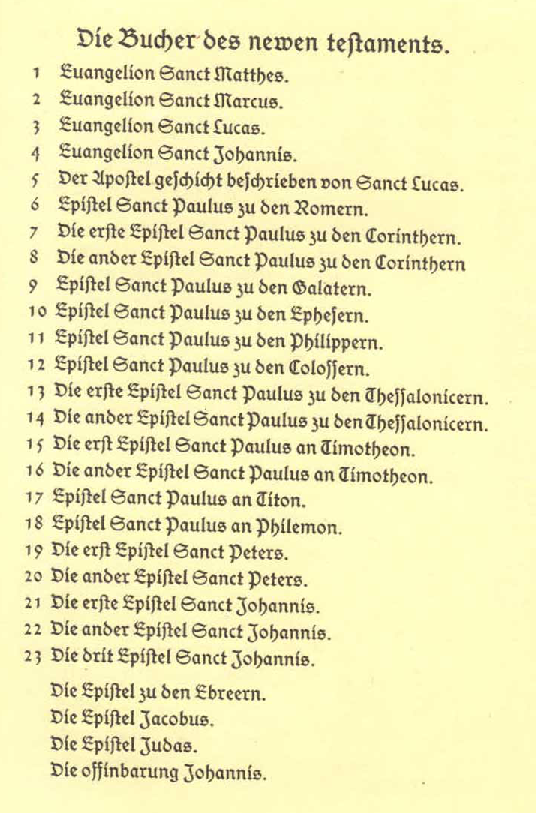

I will now summarize these three distinct epochs. The first epoch was the canonization of the New Testament, when the New Testament books were gathered together for the first time c. 400 C.E. There were earlier isolated attempts to compile revealed literature that foreshadowed the New Testament canonization, such as the Muratorian fragment (which excluded James, 1 & 2 Peter and included the Shepherd of Hermas), Marcion's canon (which included only Luke, Acts and many of Paul's epistles), and other disparate lists by early church fathers. The first four centuries were turbulent and volatile times, and no consensus was established until the time of the Council of Carthage c. 397 C.E. (and other contemporary councils) when the Church consensus on the canonization of the New Testament was first established; Barth said, "it was once the task of the Church to do it, round about the year 400." [3]

According to Denzinger, The Council of Carthage (III) c. 397 C.E. defined the biblical canon as follows (notice the inclusion of deuterocanonical books, and different ordering):

The biblical canon of the Council of Carthage (397 C.E.):

The Canon of the Sacred Scripture * 92 Can. 36 (or otherwise 47). [It has been decided] that nothing except the Canonical Scriptures should be read in the church under the name of the Divine Scriptures. But the Canonical Scriptures are: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings, Paralipomenon two books, Job, the Psalter of David, five books of Solomon [i.e. Proverbs, Song of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, Wisdom of Solomon, and Sirach], twelve books of the Prophets, Isaias, Jeremias, Daniel, Ezechiel, Tobias, Judith, Esther, two books of Esdras, two books of the Machabees.

Moreover, of the New Testament: Four books of the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles one book, thirteen epistles of Paul the Apostle, one of the same to the Hebrews, two of Peter, three * of John, one of James, one of Jude, the Apocalypse of John. Thus (it has been decided) that the Church beyond the sea may be consulted regarding the confirmation of that canon; also that it be permitted to read the sufferings of the martyrs, when their anniversary days are celebrated. [4]

The second epoch, when the biblical canon was reopened, was at the time of the Council of Florence in 1441 C.E. after the Great Schism, when the Catholic Church was forced to define the biblical canon (and everything else) in response to definitions from the Eastern churches.

The third epoch was not long afterwards, when the Protestant Reformation again opened the biblical canon for radical changes. The Old Testament books—such as Judith, Solomon, Tobias, Sirach and 1 & 2 Maccabees—had been in the biblical canon for a thousand years, were suddenly cast out!

Karl Barth cites Denzinger's entry #706 from the Council of Florence (1441) and #784 from the Council of Trent (1546, Session IV), so here is the source from Denzinger that Barth quoted showing how the bible from the first 1500 years of Church history is substantially different from the sixty-six books in most Protestant bibles today:

The biblical canon of the Councils of Florence (1441 C.E) and Trent (1546 C.E.):

Books of the Old Testament: The five books of Moses, namely, Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy; Josue, Judges, Ruth, four books of Kings, two of Paralipomenon, the first book of Esdras, and the second which is called Nehemias, Tobias, Judith, Esther, Job, the Psalter of David consisting of 150 psalms, the Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the canticle of Canticles, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Isaias, Jeremias with Baruch, Ezechiel, Daniel, the twelve minor Prophets, that is Osee, Joel, Amos, Abdias, Jonas, Michaeas, Nahum, Habacuc, Sophonias, Aggaeus, Zacharias, Malachias; two books of the Machabees, the first and the second.

Books of the New Testament: the four Gospels, according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; the Acts of the Apostles, written by Luke the Evangelist, fourteen epistles of Paul the Apostle [n.b. Hebrews is not attributed to Paul], to the Romans, to the Corinthians two, to the Galatians, to the Ephesians, to the Philippians, to the Colossians, two to the Thessalonians, two to Timothy, to Titus, to Philemon, to the Hebrews; two of Peter the Apostle, three of John the Apostle, one of the Apostle James [n.b. James is placed near the end of the list], one of the Apostle Jude, and the Apocalypse of John the Apostle. [5]

It's fascinating that the book of James was excluded from the earliest biblical canons (i.e. Muratorian fragment), and was placed after 3 John for 1500 years (including the Council of Florence, Council of Trent, and also in an appendix of Luther's Bible), and it is now considered one of the oldest books in the New Testament and is placed after the Epistle to the Hebrews. This book of James is a testimony to the ongoing openness of the biblical canon.

It's important to add, that Barth does not believe that New Testament was canonized because this Council of Carthage, or Florence, or Trent or any other official church body, or a pope, or any individual admitted these books into the biblical canon, but rather that this time was when the Church collectively recognized that these books contained the self-revelation of God and collectively witnessed to them. (Perhaps the New Testaments were not widely available until c. 400 C.E. as well). In other words, the Holy Spirit moved the whole Church circa 400 C.E. to recognize the biblical canon now included the New Testament (in addition to the Hebrew Bible). Karl Barth compared the the canonization of the New Testament to the Samaritan women in John 4, who first witnessed Jesus first hand, and then told her friends about Jesus. At first her friends believed based on the Samaritan woman's witness, but once her friends encountered Jesus directly, they no longer needed the Samaritan women's testimony to believe (John 4:42). The truth of Jesus did not depend on the Samaritan women's truthful witness to Jesus, but it was essential nevertheless for others to recognize Jesus also. Likewise, there were many early witnesses to the revealed books before they were canonized, but once the books of the New Testament were made known, then the entire church witnesses to their truth and canonization. The main point is that the self-revelation of God is not conditional upon any person's approval (c.f. John 1:12-13).

The Protestant biblical canon is a novel departure from the previous 1500 years of church history

It's a myth that the Protestant Reformers excluded books (i.e. the Apocrypha) because they were never part of the canon, or because they were mere accretions added by a corrupted church that never belonged. A golden tablets myth has been perpetuated in evangelical circles (particularly by those who propose dictation theories of inspiration) that describes the bible as if it had descended from heaven on sixty-six golden plate all at once, or that each of the sixty-six books of the Protestant bible descend incrementally from heaven, one golden plate at a time in seamless harmony. This myth is demonstrably false by reviewing the sources that I shared from Denzinger (#92, 706, 784) that was cited by Karl Barth (and also falsified by the fact that the Greek New Testament's eclectic text changes every year, including 34 changes to the catholic epistles alone in the NA28, and by the fact that the exact contents of each biblical book is still unknown). Denzinger proves that the canon has always been influx, with books being modified, added, removed and rearranged over the first 1500 years of church history, and that the Reformers removed books from the biblical canon that had been in it for a thousand years (i.e. 1 & 2 Maccabees, etc). The Reformers didn't reject only the Old Testament "apocrypha", they also rejected many books (and their ordering) of the sixty-six books in the Protestant biblical canon today. For instance, the Reformers rejected Hebrews, James, Jude, Revelation, 2 & 3 John, and 2 Peter, and this shows that the current Protestant biblical canon was a novel departure from the previous 1500 years of church history.

Karl Barth shows the radical criticism and reconstruction the New Testament canon underwent in the Protestant Reformation as follows:

But even the question of the New Testament Canon seemed to be reopened at that time. It is well known what Luther thought about Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation. He did not wish to deprive anyone of them, but for his own part he could not number them with the “right, sure, principal books.” What is not so well known is that in the table of contents of his September Bible of 1522 he openly separated them from the other twenty-three and according to him true New Testament writings, thus characterizing them at once as deuterocanonical. And Luther did not stand alone.

Before the Council of Trent with its new tradition, not only Erasmus but even Cardinal Cajetan expressed open doubts concerning the authenticity and authority of Hebrews, James and Jude as well as 2 and 3 John. Zwingli thought especially that the Apocalypse should be rejected. And it is at least noteworthy that Calvin omitted the Apocalypse in what was otherwise a complete exposition of the New Testament. From his introductions to the commentaries it emerges clearly that he had doubts not only concerning the books mentioned by Luther but also concerning 2 Peter and 2 and 3 John. [6]

Despite the turbulent and volatile history of the canon, Karl Barth ultimately decides against tradition and sides with the sixty-six books of the Protestant bible--a surprising conclusion too! But also, not surprising at the same time, because the canon is not established upon human authority but upon the uncontrollable movements of the Holy Spirit (John 3:8).

A future re-opening of the biblical canon

Barth believes that the discovery of lost epistle from Paul may cause a future epoch, when the biblical canon may be reopened, and the discovery of a lost epistle may change our understanding of the entire biblical canon, and cause other books to be added, removed or modified due to the ramification of this hypothetical discovery. We have many examples in the bible, where lost books of the bible are mentioned, and there's a very real possibility that we may one day discover one of these lost books, like when the Dead Sea Scrolls were found after quietly sitting in clay pots in the Qumran caves. (Remember that the ancient cave paintings of Lascaux were found after 17,000 years.)

Karl Barth wrote, ". . . the Church can and must continually ask concerning the legitimacy of the traditional Canon. But if it can and must do this, as in fact it always does, then we cannot rule out a consideration of the possibility of an open alteration in its constitution, either a narrowing as in the 16th century or an extension. We know that there once existed an unknown letter of Paul to the Laodicaeans, and two letters of Paul to the Corinthians no longer extant. There are also some known but “unrecorded” sayings of Jesus, unrecorded, that is, only in the canonical Gospels. And for all we know—and certain recent discoveries ought to prepare us for any eventuality—there may be things awaiting us in the sands of Egypt, in the light of which not even the Roman Church will, perhaps, one day—i.e., the day of their discovery—be able to accept responsibility for dogmatically insisting upon the concept of a closed Canon. Yet it is not the consideration of possibilities such as these, but the basic consideration of the positive nature and meaning of the Canon, which forces us to re-accustom ourselves to the thought that the Canon is not closed absolutely." [7]

Conclusion

The biblical canon as we know it today is very relatively closed, but in the future there is a very real possibility that it may burst open again, as it has in various epochs in the past, such as happened at its initial formation circa 400 C.E., and during the conflict between the eastern and western churches in the 15th century, and also during the Protestant Reformation. Maybe another epistle from Paul's to the Laodiceans or Corinthians will be discovered in the distance future, possibly 20,000 or 30,000 years in the future (like the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls or the ancient cave paintings of Lascaux), that will cause another radical revision of the biblical canon, or maybe another epoch event in church history will happen, like the Protestant Reformation or the Great Schism, that will cause the biblical canon to be shuffled, or return the Shepherd to canonicity, or remove again books such as Hebrews, James, Jude, Revelation, etc. If past trends, predict future reality, than the traditional answer is that the biblical canon is relatively closed for the moment, and its dormancy may last for centuries or millennia, but exploding like a volcano again, with anew moment of radical openness.

Sources:

1. Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics: The Doctrine of the Word of God, Vol. I/2, trans. Bromiley, G. W., & Torrance, T. F. London; New York: T&T Clark. 2004. Print. p. 476. [Bold added for emphasis]

2. Ibid. 476.

3. Ibid. 473.

4 Denzinger, Sources of Catholic Dogma #92 http://patristica.net/denzinger/#n1

5 Denzinger, Sources of Catholic Dogma #706, #784 http://patristica.net/denzinger/#n700

6. Ibid. Barth. pp. 476–477.

7. Ibid. Barth. 478

5. Header Background: Jefferson Bible, wikipedia

Related: biblical canon, canon, CD I/2, Church Dogmatics, Church Dogmatics I/2, closed canon, Karl Barth, Marcionite canon, Muratorian fragment, open canon

May 24th, 2020 - 18:45

“And for all we know—and certain recent discoveries ought to prepare us for any eventuality—there may be things awaiting us in the sands of Egypt, in the light of which not even the Roman Church will, perhaps, one day—i.e., the day of their discovery—be able to accept responsibility for dogmatically insisting upon the concept of a closed Canon.”

This is more or less what the Book of Mormon claims to be, albeit from the Americas rather than from Egypt: an ancient record of God’s dealings with men, in this case descendants of the tribe of Joseph, who left Jerusalem around 600BC (shortly before the Babylonians destroyed the city) and sailed to the American continent, where they established a great nation for a thousand years. The prophets among them testified that Christ would come, and He visited them after His Resurrection, and they wrote down all these things, before sadly falling away into apostasy and darkness. The last prophet among them buried a small record of their history and prophecies, so that future generations could have it.