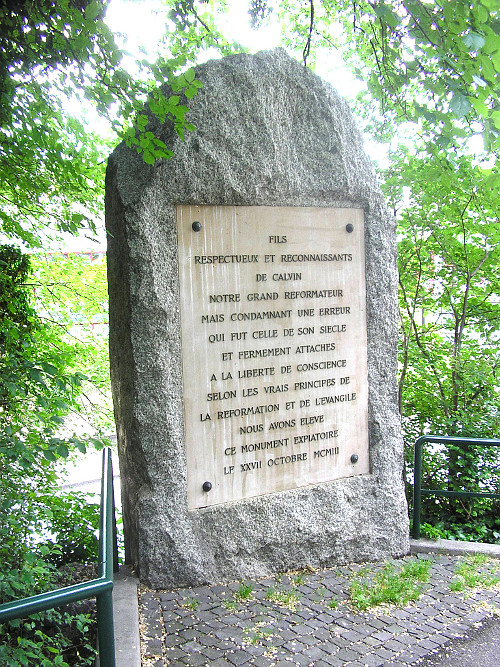

In defense of Calvinists: A memorial to Michael Servetus

John Calvin has wayward sons who still defend the execution of Servetus and Calvin's participation in it, however most Calvinists today admit that Calvin erred in the Servetus affair, and some Calvinists today are willing to admit that Calvin sinned and that Calvinism bears this burden. The exemplary response to Servetus' wrongful death was enacted by Genevan Calvinists who setup a memorial to Michael Servetus on October 27th, 1903 in the gates of Champel in Geneva, which was intentionally on the 350th anniversary to the day of Servetus' execution in the very same place Servetus was burned alive at the stake.

In Henry Beveridge's translation of the Institutes of Christian Religion IV.20.16 there is a footnote that described this memorial event: "today there is a monument on Champel, the hill upon which Servetus perished in the flames. It was erected on the 350th anniversary of the execution, by followers of Calvin." [1] The Calvin scholar, Ronald Wallace provides a description and translation of this monument to Servetus: "In 1903 a committee from the Reformed Churches set up a granite monument to Servetus at the place of his death and inscribed: 'Respectful and grateful sons of Calvin, our great Reformer, but condemning an error which belonged to his century and firm believers in freedom of conscience according to the true principles of the Reformation and the Gospel, we have raised this expiatory monument.'" [2].

The Servetus monument and its engraved inscription provide a model response for Calvinists to follow today, because the Genevan Calvinists identify themselves as heirs and admirers of Calvin life and work, yet these Calvinists also admit that Calvin gravely erred in participating in the capital punishment of Servetus, and they recognize a shared guilt in the actions committed by John Calvin. The Genevan Calvinists provide a model response that Calvinists today may admire and imitate. The Servetus monument is also a tangible reminder, that true Calvinists, do not absolve Calvin of all guilt in Servetus' wrongful death, or shamefully defend the death of Servetus or any heretic today. Every time I hear a so-called Calvinist today make a horrific defense of the burning of Michael Servetus or any heretic, I remember the Monument on Champel and the contrite Geneva Calvinists who raised this memorial in 1903, and believe these so-called Calvinists today betray John Calvin's life and work, and bring shame and disgrace upon Calvinism and Calvinists everywhere.

In defense of Calvinism: The Institutes opposed executing heretics

John Calvin's theology is a judgment upon Calvin's actions in the execution of Servetus, because Calvin's own theology prohibited the execution of heretics. In the 1543 Latin edition of John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion—the same edition he gave to Michael Servetus when they met face-to-face in 1546—Calvin teaches that the severest punishment that should be executed upon a heretic is excommunication and that the sword (especially in capital punishment) should not be used against heretics so that the church does not become a laughing stock. Calvin sadly fulfilled his own prophecy by participating in the execution of Servetus and this has left a black-mark upon Calvin and Calvinism to this day. Bruce Gordon famously said that "for many, the execution of Michael Servetus in Geneva has defined John Calvin's posthumous reputation." [3]

In defense of Calvinism, which may be defined as the theological system expounded in John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion (and not the T.U.L.I.P.), it explicitly teaches that heretics must not suffer capital punishment, and the most severe punishment Calvinism allows for heresy is excommunication. So John Calvin deviated from his own Calvinism when he participated in the execution of Michael Servetus! Henry Beveridge writes in a footnote of the Institutes IV.20.16: "It is truly unfortunate that these sound sentiments were not heeded by Calvin himself, when, exactly six years before this definitive edition of 1559 was published, he asked the councils of Geneva to arrest the heretic Michael Servetus." [4]

Ford Lewis Battles translates this section of the Institutes IV.20.16 as follows (I've added bold for emphasis):

First, this is the aim of ecclesiastical jurisdiction: that offenses be resisted, and any scandal that has arisen be wiped out. In its use two things ought to be taken into account: that this spiritual power be completely separated from the right of the sword; secondly, that it be administered not by the decision of one man but by a lawful assembly. Both of these were observed when the church was purer [1 Cor 5:4-5].

Now the holy bishops did not exercise their power through fines or prisons or other civil penalties but used the Lord's Word alone, as was fitting. For the severest punishment of the church, the final thunderbolt, so to speak, is excommunication, which is used only in necessity. Now, this requires no physical force but is content with the power of God's Word. In short, the jurisdiction of the ancient church was nothing but a declaration in practice (so to speak) of what Paul teaches concerning the spiritual power of pastors. "A power has been given us," he says, "to destroy strongholds, to level every pinnacle that vaunts itself against the knowledge of God, to subjugate and take captive every thought to the obedience of Christ, being ready to punish every disobedience." [1 Cor. 10:4-6 p.] As this is done by the preaching of the doctrine of Christ, so, in order that this doctrine may not be a laughingstock, those who profess themselves of the household of faith ought to be judged in accordance with what is taught. That cannot be done unless there be joined with the ministry the right to call those who are to be admonished privately or be more sharply corrected; also the right to bar from the communion of the Lord's Supper those who cannot be received without profaning this great mystery.

(Institutes IV.xx.16) [5]

John Calvin deviated from his own theological system as his conflict with Michael Servetus escalated. After Calvin met Servetus face-to-face in 1546, he wrote a separate treaty On Scandals in 1550, that argued that the magistrate was justified in executing heretics that injured the reputation of the church or the state, and it included a full page condemnation of Servetus. Another deviation was in the definitive 1559 Latin edition of the Institutes of the Christian Religion (published six years after Servetus was executed) wherein Calvin adds this concluding comment that partially retracts his limitations on punishing heretics: "Therefore, while Paul says in another place that it is not ours to judge strangers [I Cor. 5:12], he subjects the children of the church to censures to chastise their vices, and he then implies that there were then judgments in force from which no one of the believers was immune." (Institutes IV.xx.16; 1559 ed.) Nevertheless, Calvinism as represented by the definitive 1559 Latin edition of the Institutes of the Christian Religion's reputation is injured by Calvin's actions against Servetus, but the Calvinism system may be invoked against Calvin to redeem it.

In Defense of John Calvin

In this series, I explained that John Calvin is culpable for the execution of Michael Servetus, a sin that the whole world of his time approved. Servetus was committed to a radical theology, and he directed it specifically against Calvin, and Calvin was forced to respond to an obstinate and persistent foe. Calvin wanted Servetus to recant, not to die, but when Calvin was faced by the perilous life-and-death situations of the early Reformation, he capitulated to a world that believed heretics should be executed, and Calvin modified his own theology to conform to this worldview of his age due to tremendous political pressures he faced in Geneva. Servetus was executed by the Genevan magistrate through due process of law and not by Calvin's sole command, but with Calvin's blessing and assistance as a key witness in prosecution of Servetus (as Beveridge described). After the verdict, Servetus received a more severe sentence than Calvin expected, and Calvin protested the Genevan Council's sentencing Servetus to be burned alive at the stake, and requested a beheading instead, but he was overruled. Calvin could not bear to watch the inhumane execution of Servetus and spent that hour in prayer instead. Considering the whole story of John Calvin's twenty year fight to the death with Michael Servetus, I believe that we may condemn Calvin's involvement with Servetus, and still marvel at John Calvin's theological and ecclesiastical accomplishments like the Genevan Calvinists in 1903.

A Eulogy to Michael Servetus

This series' title Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic and Martyr is based on the header "Saint Servetus, Heretic and Martyr (1553)" [6] from Bernard Cottret's Calvin: A Biography. Cottret says "What distinguishes a saint from a martyr in popular opinion? Did not determination to make Servetus a heretic contribute, on the contrary, to plaiting him a crown? The remembrance of Servetus persisted in Geneva in the years that followed his death at Champel." [7]

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 1: Burned Alive at the Stake)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 2: A Person Condemned by the Whole World)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 3: A Radical Theology)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 4: A Twenty Year Fight to the Death with John Calvin)

- Michael Servetus: Saint, Heretic, and Martyr (Part 5: A Defense of John Calvin and the Calvinists)

Sources:

1. Henry Beveridge, Institutes of the Christian Religion, 1850. Institutes IV.20.16 footnote #587

2. Ronald S. Wallace, Calvin, Geneva and the Reformation: A Study of Calvin as Social Reformer, Churchman, Pastor and Theologian, Wipf & Stock Publishers: 1998, Eugene. Print. p. 77.

3. Bruce Gordon, Calvin, Yale University Press: 2009, Great Britton, Print. p. 217

4. Beveridge. Ibid.

5. John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion. Ed. John T. McNeill. Trans. Ford Lewis. Battles. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster, 1960. 1217. Print.

6. Bernard Cottret, Calvin: A Biography, T & T Clark: 2000, Grand Rapids. Print. p.213.

7. Cottret. Ibid. p. 225.

8. Image source for 1903 Monument on Champel (source: wikipedia). French inscription reads: "fils respectueux et reconnaissants de calvin notre grand reformateur mais condamnant une erreur qui fut celle de son siecle et fermement attaches a la liberte de conscience selon les vrais principes de la reformation et de l'evangile nous avons eleve ce monument expiatoire lf xxvii octobre mcmiii"

Leave a comment