In Jürgen Moltmann's systematic contribution The Way of Jesus Christ he argues that the resurrection of the body will include all its transitional forms from death to conception. A human being's body will simultaneously be raised as an adult, adolescent, child, infant, fetus, embryo, etc. and all forgotten memories and life experiences will be restored that have long been forgotten. I listed the human development stages backward ( in kind with Moltmann's theme that in the end, is the beginning) because the later forms of the body do not exist without having transitioned through the previous form -- every adult was once a fetus. The ethical implication of Moltmann's argument is that unborn children must be affirmed as being human beings and they may not be reduced to "human material" without condemning all forms of the body as "human material". Likewise, incapacitated people (e.g. a person with brain death) must be acknowledged as human beings.

The resurrection of the body includes its transitional forms

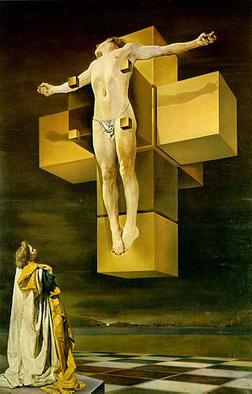

It is difficult to visualize a contemporaneous resurrection of the body in all his developmental stages in the same way that is difficult to visualize a tesseract (that oddly resembles the cross) or other fourth-dimensional objects. It's much easier to think of the resurrection as a resuscitation of the body in its last form that extends a person's lifeline beyond their death into infinity and beyond. Moltmann (like Karl Barth and many others) reject the idea of an afterlife, instead, he argues that the resurrection is an eternalized restoration of their entire life.

It is difficult to visualize a contemporaneous resurrection of the body in all his developmental stages in the same way that is difficult to visualize a tesseract (that oddly resembles the cross) or other fourth-dimensional objects. It's much easier to think of the resurrection as a resuscitation of the body in its last form that extends a person's lifeline beyond their death into infinity and beyond. Moltmann (like Karl Barth and many others) reject the idea of an afterlife, instead, he argues that the resurrection is an eternalized restoration of their entire life.

"Hope for the resurrection of the body is not merely a hope for the hour of death; it is a hope for all the hours of life from the first to the last. It is directed, not towards a life 'after' death, but towards the raising of this life. If the whole human being is going to rise, he will rise with his whole life history, and be simultaneous in all his temporal Gestalts, and recognize himself in them. What is spread out and split up into its component parts in a person's lifetime comes together and coincides in eternity, and becomes one. If what is mortal puts on immortality, its mortality is ended and everything past becomes present."[1]

For instance, a person cannot be captured by a photograph or a photo album with many photographs from key moments of their life. A human being at the present moment is a culmination of all the past moments in their lifetime. As our memories fade and we forget experiences from our past, then part of ourselves dies as well. So Moltmann argues that the resurrection must raise all stages of our lifetimes and our memories and experiences from the past must be raised too so that we fully identify with ourselves.

"As long as a person can identify himself with himself in the transmutations of the times of his life, and as long as he is prepared to do so, he is a person. If he begins to deny himself or forget himself, he destroys his personhood and no longer knows who he is. He then loses his reliability and authenticity for other people too. No one knows who he is any longer."[2]

The unborn as human beings and not only human material.

It is fascinating to imagine that in the resurrection, our memories from before birth and early childhood will be restored to us.

"Because the hope of resurrection embraces the human being's whole life history, this person will remember his past temporal configurations, and will be able and willing to identify himself with them. He will not view any one of them as a mere preliminary stage to what he is at present. Each temporal Gestalt has the same dignity in God's sight, and hence the same rights before human beings." [3]

Moltmann argues that personhood is a unity of all "diachronically in the transmutations of their temporal Gestalts." [4] An unborn child does not become a human being at the moment of birth. A person is not identified with any one stage of human development and so a human being is a unity of all their developmental stages, even before birth.

"Being human is not merely a differentiated unity of body and soul. It is also personhood in a history. The human person goes through a whole series of temporal configurations or Gestalts which can be distinguished from one another, but in which the person's identity must be preserved. The human being begins as a fertilized ovum, becomes an embryo, a foetus, a child, an adolescent, an adult, an ageing man or woman, a sick and then a dying person. Personhood is really nothing other than the continuity of the human being in the transmutations of his temporal Gestalt and the different phases of his development." [5]

All human persons were once unborn persons so unborn children may not be reduced to human material. The implication is that unborn humans must be affirmed as human beings, as well as incapacitated persons at the end of their lives.

The breach of continuity with their own earlier temporal Gestalts makes it hard for many people to recognize themselves in a fertilized ovum, a foetus or an embryo, and to concede ovum, foetus and embryo full human dignity and full human rights, even though all human beings were once in that state, and although as soon as the ovum is fertilized the human person is genetically already perfect. People then say that the foetus or embryo is human but not a person - human material but not yet a human being. Is this not inflicting death on other people and oneself? [6]

All adults were once unborn children, so to disregard any unborn human being as "human material" is simultaneously a self-condemnation and denial of our own personhood. Denying the humanity and personhood of the unborn is a death sentence upon oneself.

Every devaluation of the foetus, the embryo and the fertilized ovum compared with life that is already born and adult is the beginning of a rejection and a dehumanization of human beings. Hope for the resurrection of the body does not permit any such death sentence to be passed on life. Fundamentally speaking, human beings mutilate themselves when embryos are devalued into mere 'human material', for every human being was once just such an embryo in need of protection. [7]

Conclusion

Last month, Moltmann published a new book Resurrected to Eternal Life: On Dying and Rising at the age of 95 too! It's worth reading, because The Way of Jesus Christ: Christology in Messianic Dimensions (1990 ET) [Der Weg Jesu Christi: Christologie in Messianischen Dimensionen (1989)] was published over 30 years ago, and in this new book, Moltmann explains how his theology of the resurrection and eternal life has developed and changed. It also discusses additional relevant topics such as purgatory and the time between death and the future resurrection. It's worth reading too.

Sources:

1. Moltmann, Jürgen. The Way of Jesus Christ: Christology in Messianic Dimensions, (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), p. 267-8 Print.

2. Moltmann. Ibid.

3. Moltmann. Ibid.

4. Moltmann. Ibid.

5. Moltmann. Ibid.

6. Moltmann. Ibid.

7. Moltmann. Ibid.

8. Image of Salvador Dali's Crucifixion hypercube. Fair use, Link

9. Image of fetus used in header image By Leonardo da Vinci - http://www.drawingsofleonardo.org, Public Domain, Link

Related: Jürgen Moltmann, pro-life, Resurrection, The Way of Jesus Christ

May 23rd, 2021 - 06:30

Well, I must say these notions, while possessing some merit, come to some very sentimental conclusions, if not just plain silly. Perhaps the book says it better than does your “pro-birth” review. As I read, I kept imagining all the nice little nuclear family homes spread across the comfort zones of the world, with picket fences and a two-car garage; and within those nice little homes, all the little women being pregnant with all their little comfy offspring, and, for heaven’s sake, not one abortion, not one moment of doubt; no rape, no ill-health, no miscarriages, no struggle unto death; just a peaceful progression from womb to tomb, with some hitches, perhaps, and in the end, we’ll all be raised up to enjoy the everlasting church picnic in the neighborhood park. This has the feel of a screed to prohibit abortion, and deny women the right of choice, as difficult as those choices are, occasioned by less than optimum moments of life; if so, I’m deeply disappointed in Moltmann’s conclusions, which, at best, appear to lack grace, making the material realm and its present sadness determinative, superior, to God’s ability to renew, restore, and create anew. I.e. what has been, what is, determines what will be. While the resurrection, if such a thing exists as he envisions it, will likely capture the sum-total of everything, including rocks and trees, care needs to be exercised about conclusions: to simply move from how the end will be, to how every present moment should be, is very much like the old conundrum of “natural theology” – that whites are superior to POC, the wealthy are superior to the poor, men are superior to women, and women are child-bearers first and foremost, and so on. I think the resurrection of the dead will far more glorious, good, and grand, than that happy little middle-class event envisioned here. Anyway, Moltmann’s a brilliant writer, and perhaps your conclusions are note quite what he intended.

June 2nd, 2021 - 09:24

Hello Tom,

Thanks for reading the blog post, and I’m glad to hear you say that Moltmann is a brilliant writer. The rest of your lengthy comment is tangential to my original post and contains criticisms of things that were not discussed in the OP. You may like Moltmann’s new book that I linked to, Resurrected to Eternal Life, because it does discuss resurrection in relation to broken lives, and discusses purgatory as a possible solution. Again, I did not discuss this in this OP either.

Wyatt

February 7th, 2022 - 15:19

Moltmann appears to me to be out to lunch here. Taking a major break from reality.

He seems to be thinking about the resurrection of a dead body as somehow incorporating every stage of that individual’s physical, mental and emotional development. I can only imagine a monstrosity such as I have seen in jars in a medical museum.

What if this is not about an unimaginably weird ‘afterlife’ but about the development in the present of an element of eternal life which transcends time and space, the life of the Kingdom of God, the livingness of Eternity, of Adonai Ehod becoming Adonai Eloheinu in humanity.

Think about the difficult saying ‘Let the dead bury the dead.’ Does it mean that those whom we believe to be alive but who have no intimacy with God, are alive in the flesh and psyche only, but dead in spirit? Is it an invitation to join Jesus and choose Life over what he called death?

If it is, it is necessary to look at the way Jesus trained his disciples. . . . a training that took place over time. A training which they did not fully comprehend at any point in his lifetime, but which proceeded nonetheless and which came to a major stage of fruition at Pentecost. The result was not everlasting life in a Freak body, but a radiance of holiness which had a profound effect on contemporary Jews and subsequent human history. They did not lose their minds, they did not remember their life in the womb, they were not perfect in any way. They still had their warts, moles and missing teeth. But they Shone. . . . ‘This little light of mine’.

The evidence of Christian history is that those who are enlivened to any degree in spirit also continue to be shaped and marked by their life in body and psyche. Their life, as Paul said, has three elements: Body, Psyche and Spirit. Just look at who Paul was, who Judas was. Show me a Christian who doesn’t make mistakes and misbehave. Show me a Saint whose hagiography claims flawlessness, but who wasn’t self-critical of his or her own failings. A saint, as an old saying goes, is a spiritual treasure in a ruin. And the ruin is the part the World sees moving and believes to be alive.

What is reported here appears to me to be a complex intellectual fantasy which has no textual or practical relevance to the teaching of Jesus. Where is it in scripture?

Where?

Where?

April 6th, 2022 - 15:13

Moltmann’s resurrection paints a bleak hope for people who have lived short and miserific lives. Without hope for a life that is qualitatively superior to this life (re: all the negations of ‘this world’ in Johannine terms), such a resurrection is little more than the eternal return of misery. Where is the transformation? Is the unspeakably handicapped person only to hope for eternal handicap? Does the man born into a short, brutal life of slavery, torment, and debilitation have only those memories to relive?

If the resurrection is less than transformation to completion (could ‘putting on immortality’ be more qualitative than quantitative?), it’s hardly any good–a hope of eternal rehash seems fatalistically jejune and unworthy of our service.